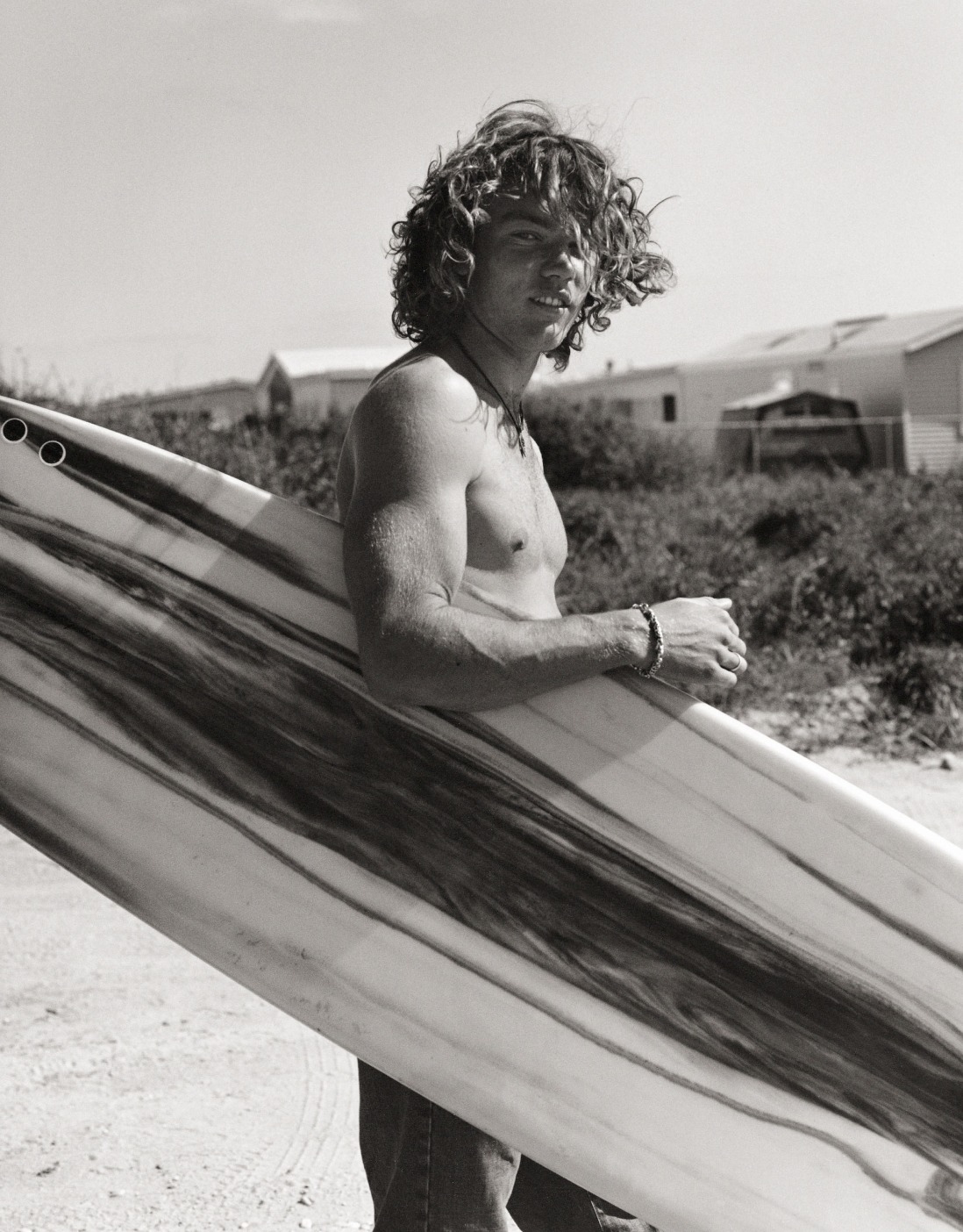

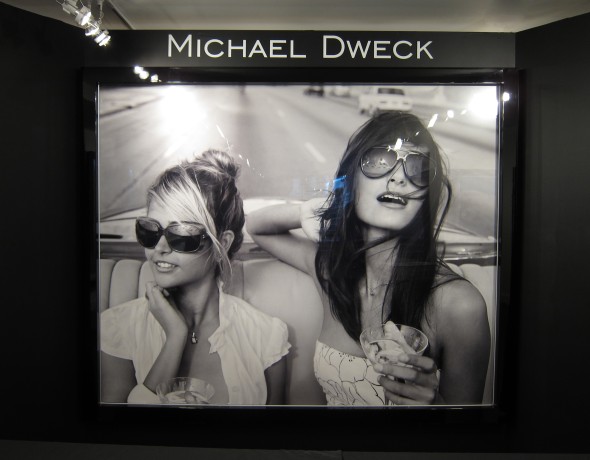

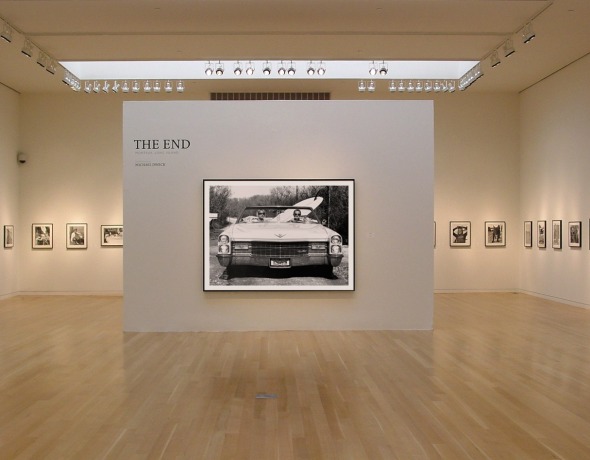

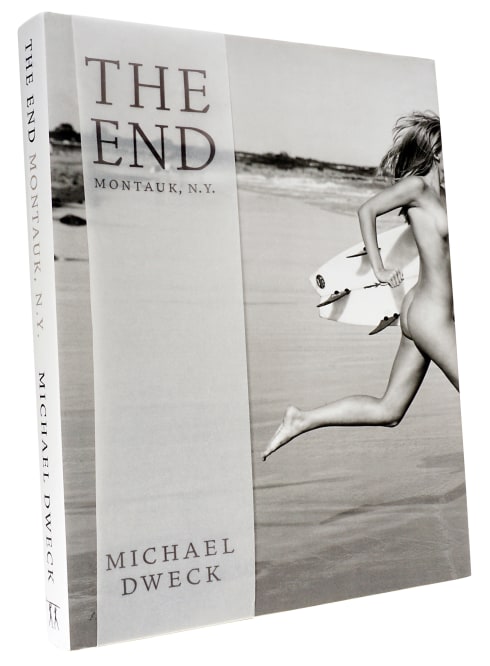

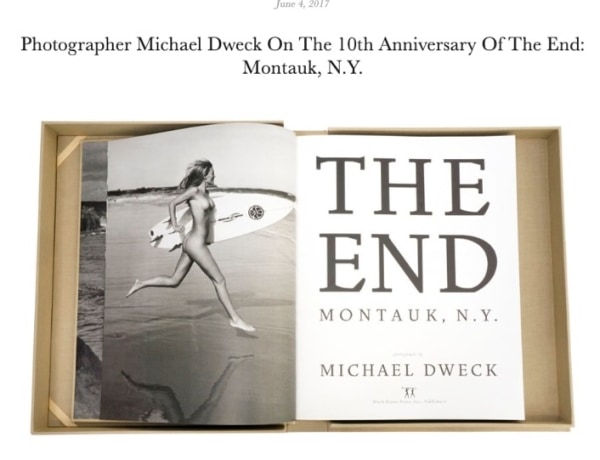

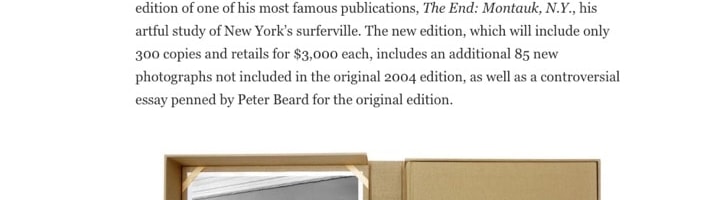

Michael Dweck’s first major photographic work was published in volume form as The End: Montauk, N.Y., in 2004, and was featured in several exhibitions and art fairs that year. The work portrays the old fishing community of Montauk and its surfing subculture. It is an evocation of a real-world paradise lost: the paradise of summer, youth, and erotic possibility — an American version of the Arcadian vision. Blending nostalgia, fantasy, and documentation the photographs present a compelling portrait of a place in time and a way of life at once fading and being reinvented with each new season.

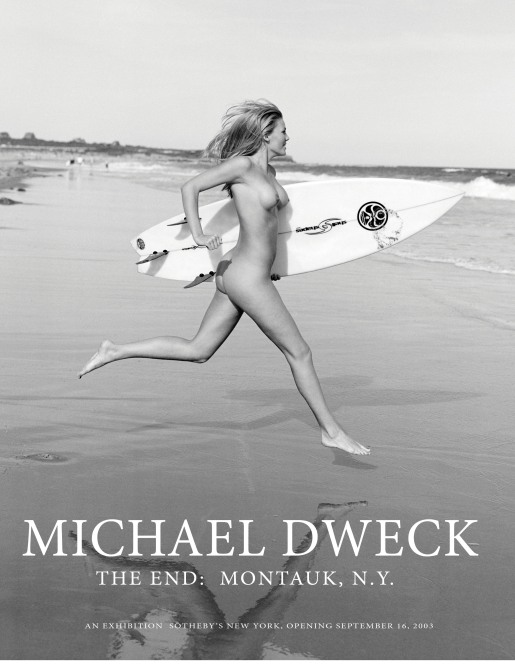

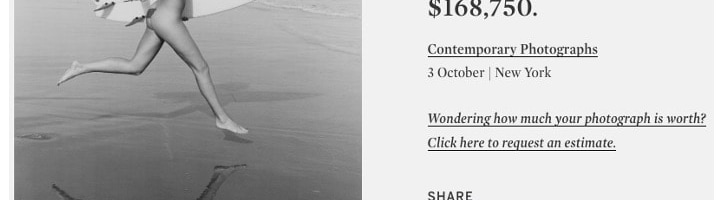

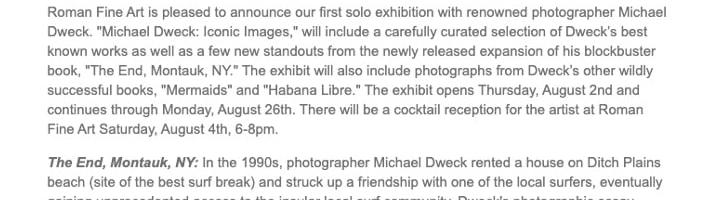

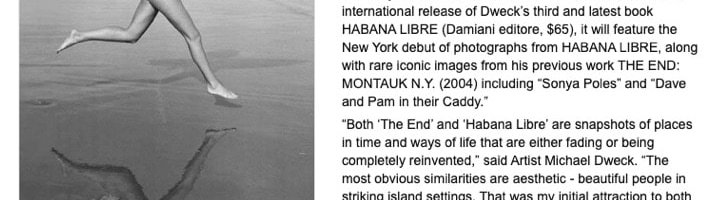

The signature photograph of the collection, Sonya, Poles, is an image of ecstatic summer. A beautiful young woman in full naked glory — her blond hair blown back, her breasts aloft, a smile of anticipation — bounds across a glistening beach, a surfboard under her arm, toward the incoming waves. In the far distance — in the upper margin of the picture — waves and dunes, surf and scrub fringe the horizon line which divides her head from her body. Her face is profiled against the great sky, and her dynamic body against the flat expanse of wet sand. All the bliss of summer fun and youthful promise is summed up by her scissor kick, reiterated by her shadow and her reflection, a vivacious “v” form that becomes a faceted diamond cleaved from light. And that bolt of white, her surfboard, like a missile, will carve out the place on the wave that will bear her back over the beating tide like a goddess from the sea.

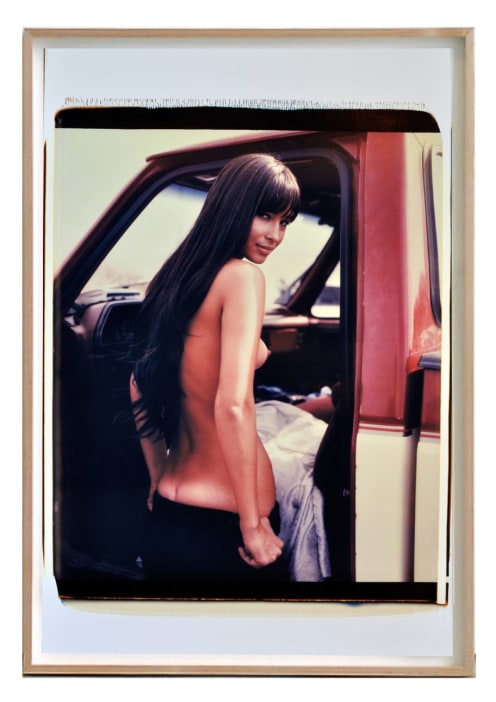

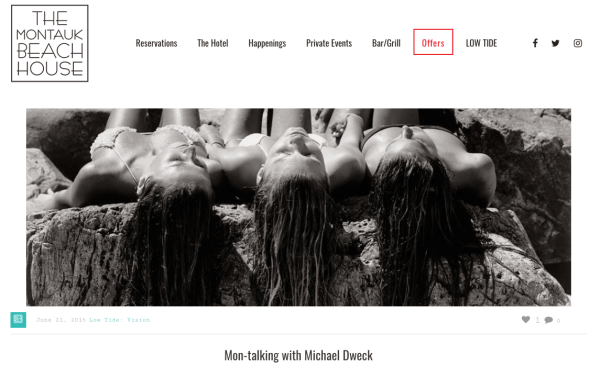

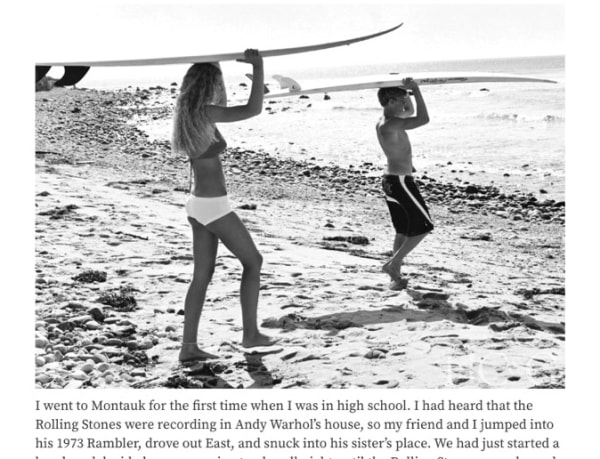

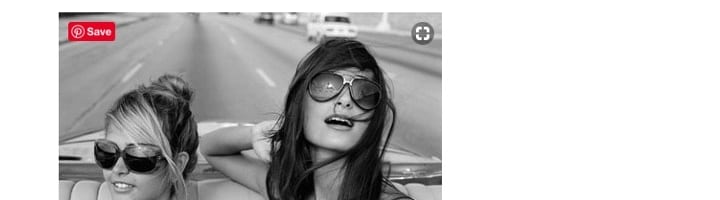

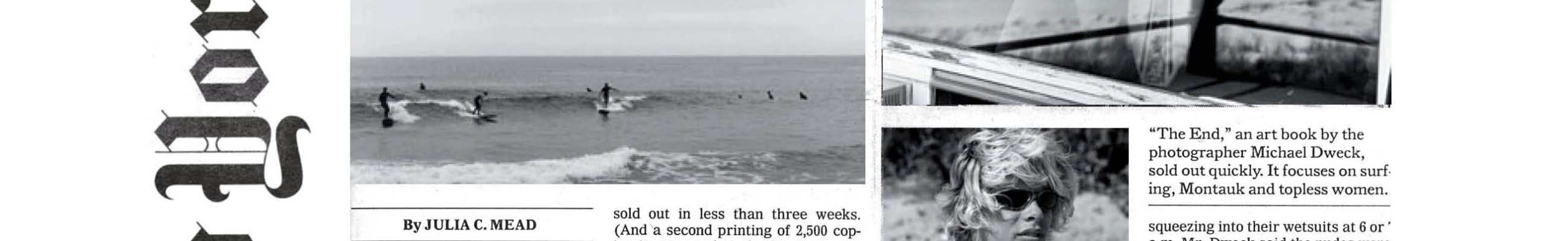

A tattered Old Glory flaps in the wind, an abandoned VW camper sits near the side of the road, beached like a dead whale, its former glory as a Love Bug long lost. Cars pull up in the parking lot near the beach. People slip out of their t-shirts and jeans and into bathing suits. The gear is unloaded. The tribe gathers. Aging sybarites ponder their past glories while oblivious, feckless youth in full flower frolics on the beach, cavorts in the water, sits out on the gentle swells waiting for waves, or makes mischief up at the motel or back at the cottage. Old timers measure the days, the years not by how far they have come, but how close they have remained and yet how much the place and they have changed, how much the weeds have grown up around them like the abandoned camper. An old surfboard, left under a house some twenty, thirty years before finds its original owner just down the road. At night the luau begins and the girls in grass skirts tease the men and boys. And the pleasures of the night beckon.

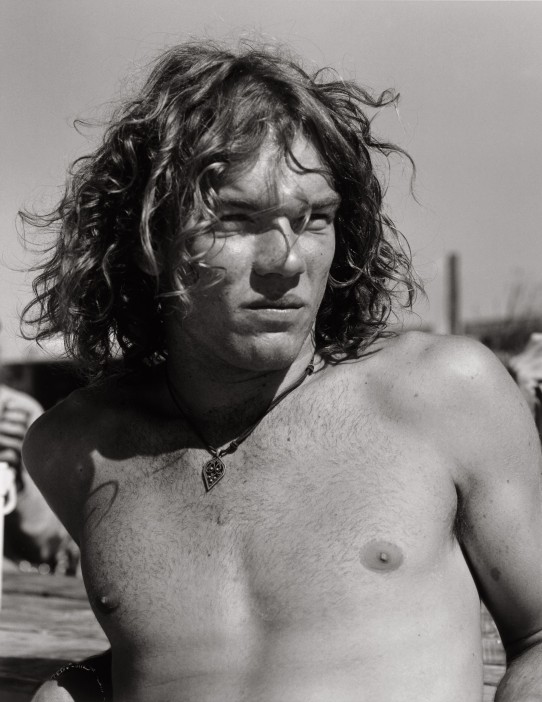

A few old timers show up, hang out, nowhere else to go, not part of the party but regulars on the scene. They add a little texture, lend a bit of character – like relics and artifacts – and are tolerated, at times perhaps indulged, as long as they don’t bother the girls. They serve as reminders that the past is not just the sound of receding trumpets. The years roll on like the tides, the seasons turn, and each summer brings its own story. With each new year, there is some new development, new blood, and more and more the hazard of new fortunes changing the balance and tone. New arrivals take it as they find it. Only the lifers, of one sort or another, bear the burden of how things ought to be, how things used to be.

Michael Dweck’s The End: Montauk, N.Y., is a private Idaho, a personal Eden, at once remembered and imagined. The Arcadian setting is a place for recreation, self-invention, and the celebration of physical beauty and well-being and the tender temptations of the flesh. It is a down-home beach paradise of a distinctly American variety, Endless Summer, that blessed but all too brief interlude that separates the seasons of school and work, adolescence and adulthood. Dweck’s vision of the far end of the island mingles the yearnings and anxieties of youth and age, of callowness and conscience, the exuberance of one’s salad days and the frisson of old bachelors. The season in the sun in due course passes into autumn. Youth and beauty blush, exude their sweetness, exert their power, but inevitably falter and fade before the onslaught of the years under the overarching, ozone-depleted sky. Our times are not in our hands. The eviction notice is tied to the gate, even as one enters, and the unease of that knowledge hovers over the good fun. The golden youth of one summer is the worldly-wise veteran or the broken old timer of another. The End is an elegy to the evanescence of youth and an ode to the consolation of art.