Michael Dweck: Forever Young

Digital Photo Pro

04/05/2012

Back

By William A. Sawalich

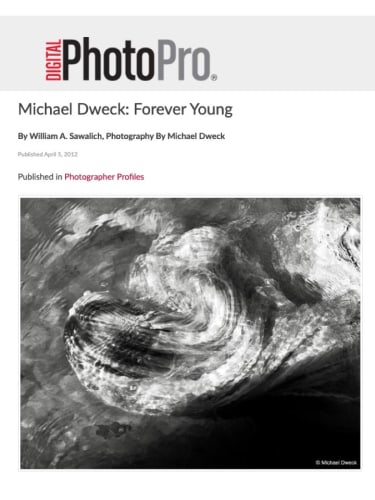

"Montauk" and "Mermaids" make up the bulk of Dweck’s photographic career. His first project, "The End," was centered on a Long Island beach community and initiated as a commercial portfolio to garner assignments. But the subject resonated with him, the youth inspired him, and his path was set.

"I try to explain the difference between focusing on youth and focusing on young people," he says, "but it’s lost on many. I’ve described it as the difference between boiling water and steam, but that doesn’t really clear much up. I just like the idea of what youth represents and how a well-framed photograph can capture that essence and make it last forever. The irony, of course, is that you’re preserving something ephemeral, but that’s what makes it particularly poignant for me. So much of my vision is about getting the hell out of where we are at a particular time and reflecting on where we want to go and why. So youth is a big part of that, particularly that segment of youth; that age where you stop wishing you were older and aren’t yet wishing you were younger. Your dreams stop involving where you are and start encompassing what you want to do and where you want to do it. And that’s a beautiful point from which the rest of your life will bloom—though you don’t always see it that way at the time. To see images of that exact moment, I think, can take you back to that place—and maybe from there, you can think magically again and stop wasting time on wishes."

Dweck’s most recent project "Habana Libre," unlike "The End" and "Mermaids," does contain an element of documentary realism. "There’s this really complex circle of privileged artists," he says, "a farándula. It’s all real. This wasn’t quite like ‘Montauk,’ which was all carefully controlled scenes. That’s why I had to make eight separate trips to Cuba—I wanted ‘Habana Libre’ to be a narrative about real people in a real place and a real time. At the same time, though, I never wanted to present it as ‘documentary.’ Yes, it documents something, but so does Gone with the Wind. And I don’t know anybody who would call Gone with the Wind a documentary.

"The point," Dweck continues, "is that the project was never meant to be about Cuba. It was meant to take place in Cuba. It was meant to be Cuba—my ideal vision and impression of it anyway. The only intention I had in crafting this narrative was to capture a story of an island and a certain group as I envisioned them. There are plenty of ways to read ‘Habana Libre,’ and I’m not suggesting any are wrong. But when it comes down to it, it’s a work of art about a very particular story arc involving a very unique group of people. I love when people explain to me their interpretations of the work; I’m just not keen when they explain my intentions to me."

The line between truth and fantasy, documentation and fiction, is an important one. Dweck adheres to that constantly, and bristles at the idea that a captivating narrative must be anchored somehow to reality.

"I always find it interesting that this idea of arrangement seems to be considered more in photography than other arts," Dweck says. "There’s a large amount of ignored participation by the subjects and audiences of, say, painting or music or film. In the end, if the art is good, it can ultimately allow you to forget all that. You can interact with the art itself and not the process that created it. It takes a bit more convincing for this to work with photography, I think, but that’s what I try to do—and a big part of that begins with controlling your environment."

Though his process is controlled and the results are cinematic, Dweck doesn’t utilize a movie-style set. He prefers technological minimalism, shunning digital for film and deferring to ambient light whenever possible.

"When I shoot on film," he says, "which is probably 99 percent of the time, I try to keep a lot of camera bodies, maybe four or five, around my neck. It’s like working from a palette. So maybe I’ll have color in one or two, and the others will be black-and-white, and then I can switch as needed. I tend to set these scenes in my mind before I go about photographing them, even if I haven’t staged them outright. So once those impressions filter through, I reach for the camera that I think can best capture what’s already imprinted in my head. It doesn’t really make sense; that’s as far as I understand it, too."

"I’ll take natural light 99 times out of a hundred," Dweck continues, "especially when I’m working outdoors. It would have to be a very special scene for me to favor something fabricated when the sun is shining for free. Indoors or in low light, I might use an on-camera flash if it feels right, or I’ll just play around until I get what I want. I’ve tried everything, but kind of settled on that as the basic approach. I try not to fake anything with light. It just takes too much time and feels cheap to me. I prefer the simple setups or, in the right scenarios, something improvised—a bedside lamp or a pair of headlights. I’ve used candles in the past, the light from a projector….

I don’t care if things look beautiful, he continues. I want them to feel beautiful, feel reflective of ideas and the places in which they’re set.

"It ended up being great that I work that way," he says, "because this was the way it had to be in Cuba. I had to travel with my equipment, so that ruled out any elaborate rigs. Plus, we were constantly moving, and it was often 100° F, so big laborious lighting setups weren’t really an option. I don’t think I had anything but natural or ambient light and/or on-camera flash for anything in Cuba. It was like a ‘found-light’ treasure hunt at times. ‘Oh, there’s a car broken next to the beach—let’s hurry up and get this photograph before he fixes it.’"

A former advertising agency head, Dweck uses photography solely to serve his vision; that is, he doesn’t get caught up in technicalities. Maybe it comes from his deep understanding of advertising’s core appeal, in which authenticity—even when it’s artificially constructed—trumps all.

"As an advertising alum," he says, "I guess I understand imagery in a certain sense, and that has helped me bury suggestion in my work. Not in a subliminal sense, but in a manner that respects subtlety and really respects its audience. In advertising, too, I never wanted my work to seem too obvious or cliché. A lot of my work dealt with irony and didn’t even show or mention the product. And you can see that in my work now—not the irony so much, but the very careful exposure that isn’t reductive and makes the audience work for the win."

See more of Michael Dweck’s photography at michaeldweck.com. His newest book, Habana Libre, is available in hardcover or as a limited-edition box set with an 8×10 chromogenic print.