An unsettling fact fascinated Dweck: destructive devices like missiles and rockets can be utterly, horribly beautiful. As in the paintings of Goya or certain unflinching noir films, Dweck’s photos find pleasure amid sinister forces, as disaster looms. In his “Still Lifes” series, these instruments of devastation pose innocently against clear blue skies; in “Thrusters,” we see them in intimate detail, every panel, gear, and screw. These works update the Precisionist paintings of industrial subjects by Charles Sheeler, Elsie Driggs, and Charles Demuth, darkly. Right now in these pictures, everything is still, but we know that, with the click of a button on some distant control panel, unfathomable carnage could be unleashed.

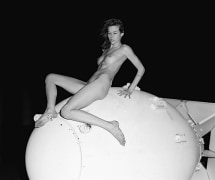

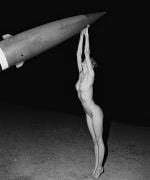

The “Bombshells” are the core of this work, with Dweck posing a woman with weapons. They stage a competition between brutal technology and flesh that no human can possibly hope to win. Intertwining sex and death, these photos allude to the enduring connection between female sexuality and military power: the rockets named for the goddesses Nike (whose domain was victory) and Artemis (hunting); the bombing of the Bikini Atoll that inspired a swimsuit name; and the countless pinups who have adorned fighter-plane fuselages. Leonard Cohen sang of “being guided by the beauty of our weapons.” In the Stones song that titles Dweck’s work, war goes from “just a shot away” to “just a kiss away.”

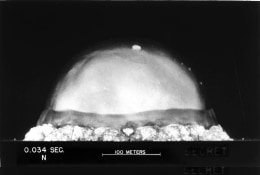

The works came about via careful persuasion and a bit of luck, with Dweck gaining access to the White Sands Missile Range in Las Cruces, New Mexico. It was here that physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer witnessed the first detonation of a nuclear device, in the summer of 1945, and thought of Vishnu’s lines from the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” The United States continues to test its aerial weapons at the site, constantly expanding its arsenal.