Truffle Hunters and the joys of ‘comfort cinema’

Financial Times

06/24/2021

Back

By Wendy Ide

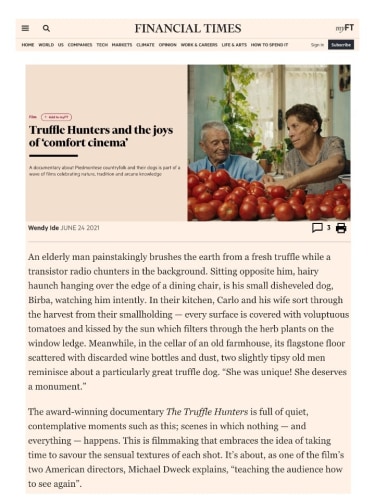

An elderly man painstakingly brushes the earth from a fresh truffle while a transistor radio chunters in the background. Sitting opposite him, hairy haunch hanging over the edge of a dining chair, is his small disheveled dog, Birba, watching him intently. In their kitchen, Carlo and his wife sort through the harvest from their smallholding — every surface is covered with voluptuous tomatoes and kissed by the sun which filters through the herb plants on the window ledge. Meanwhile, in the cellar of an old farmhouse, its flagstone floor scattered with discarded wine bottles and dust, two slightly tipsy old men reminisce about a particularly great truffle dog. “She was unique! She deserves a monument.”

The award-winning documentary The Truffle Hunters is full of quiet, contemplative moments such as this; scenes in which nothing — and everything — happens. This is filmmaking that embraces the idea of taking time to savour the sensual textures of each shot. It’s about, as one of the film’s two American directors, Michael Dweck explains, “teaching the audience how to see again”.

The Truffle Hunters premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2020, in the hazy innocence of the few final weeks before the pandemic. It was enthusiastically received at the time, reviews describing it as “sublime”. But now, nearly 18 months later, there’s an added resonance. It’s a film particularly in tune with the bruised collective psyche. It offers escapism, but not the kind that plunges us into an immersive CGI fantasy realm. Rather it is a balm, a window into another, simpler reality. This is comfort cinema in its purest form — truffle risotto for the soul.

So what constitutes “comfort cinema”? There’s an overlap with slow cinema, certainly, a movement characterised by its long meditative takes and emphasis on atmosphere over story. Proponents include directors such as Bela Tarr, who might dedicate 15 minutes to a single shot of someone sadly peeling potatoes. The movement found its apotheosis in Double Tide, a film consisting of just two shots, each 45 minutes long, of a distant figure digging for clams on a mud flat in Maine.

Comfort cinema adopts something of the languid pacing of slow cinema, but trades the punishing austerity for a more accessible and rewarding approach. Films such as The Truffle Hunters and fellow documentaries such as Honeyland, about a keeper of wild bees in North Macedonia, and Le Quattro Volte, a study of goats and herders in southern Italy, connect the audience with something that is missing from their lives: roots in tradition, and the kind of arcane knowledge that we didn’t know we needed.

There has been much speculation as to what constitutes the perfect cinema antidote to the lockdown blues — everything from Russell Crowe’s meat-sweating, vein-popping reign of destruction in the road-rage thriller Unhinged to Steve McQueen’s stolen night of partying Lovers Rock has been suggested. But Covid enforced a moment of collective reflection, a reappraisal of our ways of living. There has been a noticeable trend of city dwellers quitting the grind of urban life to get back to nature. And the spike in popularity of homespun activities such as sourdough bread baking and gardening led to nationwide yeast shortages and a boom time for online plant companies.

The Truffle Hunters, with its ancient lore, and its spry old men and their dogs scrambling through the Piedmontese woodlands, chimes perfectly with this shift in priorities. It’s a film that celebrates a rooted connection with the land, a symbiosis rather than the kind of intensive agri-industrial plundering that, if reports are to be believed, leaves us more vulnerable to pandemics in the first place.

This was certainly the attraction for Dweck and co-director Gregory Kershaw. “Greg and I have an obsession,” says Dweck. “And that obsession is to find these worlds that exist outside of globalisation and technology. Worlds that haven’t been stripped of their identity and have a connection to local history and culture.” They discovered the Piedmont region after they both, independently, holidayed there. Dweck says, “There was a sense that this was a place that was removed from the modern world. It had a very different rhythm.”

But, as they discovered over the three years it took to make the film, it was not a place that readily gave up its mysteries. “Everything in this world is a secret!” says Kershaw “We had no idea how secretive it was until we went there and tried to meet the truffle hunters. We would go to a trattoria that was serving truffles and would ask, ‘Could you introduce us to the truffle hunter you buy from?’ They said, ‘I’ve never met the guy. I put some money in a box, and the next morning, there’s a truffle in the box’.”

The bonds between the men and the dogs (which are trained to follow scents by the hunters concealing bits of Gorgonzola cheese in their turn-ups) are among the film’s main charms. Kershaw and Dweck mounted cameras on the dogs’ heads in order to capture the thrill of the hunt for the elusive white truffle. But this also gave a deeper insight into the human-canine interactions.

“There appeared to be a lengthy conversation between Birba [the dog] and Aurelio [her owner]. He was talking about Christmas — ‘I have prepared a special lunch for you . . . ’ — and Birba was paying attention. That told us something about their special relationship.” The directors recall being invited to dinner with Aurelio, and noticing that not only was there a place set at the table for Birba, but she was served first.

Food and drink are at the heart of the film, and were integral in each connection that the directors forged. “Every conversation in this region usually starts with drinking an espresso or a glass of wine.” And food provides a through-line to other examples of comfort cinema: Honeyland’s wild bee swarms is one example. Then there’s Diana Kennedy: Nothing Fancy, a portrait of the indomitable cookbook author and environmental activist, which proved to be an unexpected critical hit during the first lockdown — a brusque lecture on the finer points of guacamole-making from a fiercely posh nonagenarian proved to be oddly soothing in uncertain times. And it’s not just documentaries that qualify as comfort viewing: Kelly Keichardt’s First Cow, with its quiet domesticity, male friendship and cake baking, is a key recent example.

What makes this portrait of an embattled way of life all the more precious is that it is so precarious. “Truffles are becoming harder to find every year,” says Kershaw. “It’s climate change, the result of deforestation to make vineyards. Being able to live like that is rare. They wouldn’t call it wisdom but I think they have a deep wisdom, and they were eager to share what they know with the world.”

For their part, in addition to capturing it for posterity, the filmmakers decided to help protect the truffle traditions that so beguiled them by setting up a conservation fund which buys up land to prevent further deforestation. “We fell in love with the region,” says Dweck. “We wanted to help preserve it.”

In UK cinemas from July 9