‘The Truffle Hunters’ Will Pique Your Appetite and Push You to Dig a Little Deeper

Eater

03/05/2021

Back

The bucolic documentary, out today, follows truffle hunters and their canine companions in Piedmont, Italy

by Elissa Suh

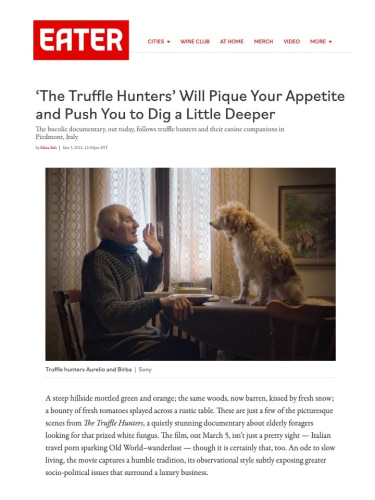

A steep hillside mottled green and orange; the same woods, now barren, kissed by fresh snow; a bounty of fresh tomatoes splayed across a rustic table. These are just a few of the picturesque scenes from The Truffle Hunters, a quietly stunning documentary about elderly foragers looking for that prized white fungus. The film, out March 5, isn’t just a pretty sight — Italian travel porn sparking Old World–wanderlust — though it is certainly that, too. An ode to slow living, the movie captures a humble tradition, its observational style subtly exposing greater socio-political issues that surround a luxury business.

Do you know who picked your truffles? The heady white ones perfumed with an unmistakable scent? It’s not who you may have thought. Carrying on cultural tradition, an eccentric group of spry septua- and octogenarians unearth Tuber magnatum, the Alba truffle, outside the small Piedmontese village of Moncalvo. Absolutely necessary for finding truffles are their canine companions. “A bad dog is like a useless degree,” says one man, who serves his dog dinner on fine china right next to him at the table. Another hunter sings to his dogs as if they were dear children. With scenes devoted to the everyday occurrences of their lives, the film is as much a food documentary as a nature one — an uninhibited and unprecedented glimpse into a vanishing world.

Shelving the expository track taken by many popular food movies and TV shows, which aim to inform viewers as much as possible, The Truffle Hunters unfolds as a series of oft-wordless vignettes. Without an authoritative presence like voiceover, explanations, or direct interviews, much is left unsaid and unexplained on the art and practice of truffle hunting. For example: What breed of dogs has the best nose? How do you train them? Who will inherit this practice in the future? These questions go unanswered, which is as much the filmmaker’s decision as it is the scrappy fruit of their limitations. Dweck and Kershaw worked on the film for three years, gaining trust and access into this little-seen subculture.

Sprinkled throughout the film are some tangential insights in the commercial life of a truffle after it’s been plucked out of the ground. Foragers negotiate with middlemen; middlemen phone clients and chefs; truffles are collected and auctioned at a fair — all gentle reminders of the capitalist supply chain. There is no market for misshapen truffles, so hunters are squeezed to find perfect specimens — which becomes difficult when the harvest relies on uncontrollable conditions. One hunter, a Saruman-looking tippler, has bowed out of the game entirely. Tapping out an explanation-cum-appeal on his Olivetti typewriter, he explains that the integrity of truffle hunting has been marred by fierce competition and foul play, including trespassing and even dog poisoning. Elsewhere, the high demand for Alba truffles has spurred a profitable and vast conspiracy of fakes.

Every frame looks like a painting. There are few tracking shots, save from some terse action footage from the dog’s POV. The filmmakers plant the stationary camera in front of their subjects, which gives them a status akin to noble portraiture. This is cultural preservation through filmic documentation, a record of unsung heroes — the lowest totem on a luxury food chain. Divorced from technology, the foragers may not be interested in watching the final product, but it’s likely they wouldn’t be phased by such adulation. Bereft of leading questions or heavy-handed suggestions, The Truffle Hunters allows introspection and asks the viewer to come up with their own conclusions. It’s a movie that fosters your curiosity — piques your appetite, if you will — and pushes you to dig a little deeper.