‘The Truffle Hunters’ Directors on How They Filmed a Secretive, Vanishing World

Variety

11/25/2020

Back

By Pat Saperstein

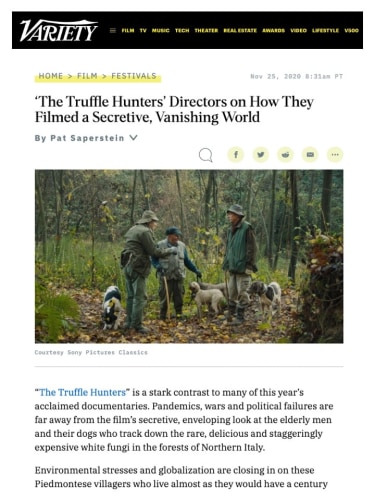

“The Truffle Hunters” is a stark contrast to many of this year’s acclaimed documentaries. Pandemics, wars and political failures are far away from the film’s secretive, enveloping look at the elderly men and their dogs who track down the rare, delicious and staggeringly expensive white fungi in the forests of Northern Italy.

Environmental stresses and globalization are closing in on these Piedmontese villagers who live almost as they would have a century ago, with little reliance on digital technology. As the men wind down their lives combing the forests to supply far-flung restaurants, generations of knowledge might be at risk of fading away into an earthy-smelling pile of truffle dust.

It’s that vanishing world that Gregory Kershaw and Michael Dweck wanted to capture in “The Truffle Hunters.” The documentary was first presented at IDFA’s production forum a few years ago, premiered at Sundance and is set to open through Sony Pictures Classics in the U.S. on Dec. 25, depending on shutdowns. It also racked up several nominations for the IDA awards, including best documentary and best director.

Kershaw, who has a background in environmental documentaries, and Dweck, a visual artist and filmmaker who started as an advertising creative director, previously collaborated on “The Last Race,” which also looked at a specific culture on the verge of disappearing – in that case a small-town racetrack.

The documentary forgoes narration and hard facts to plunge the viewer into the small part of Italy where the rare truffles are found around the roots of trees. Single-frame shots of the hunters in their rustic homes are interspersed with visceral treks through the forest, some from a dog’s eye view, and glimpses into the world of selling the costly orbs on the world market.

“It’s not so much about conveying information. We let the world sort of wash over them, and through that process, hopefully they feel it and understand it, and are brought into it to experience it,” says Kershaw. “We didn’t have a story – it was just this place, and this mystery.”

When the co-directors heard about the mysterious truffle hunters while travelling in the region, they realized tracking them down and documenting their lives could make a compelling film. Letizia Guglielmino, who came on as translator and then became a co-producer, was key to helping get the old men to trust the filmmakers, who hung out with the men, eating lunch, drinking wine and observing their lives over the course of three years.

“She helped us very slowly get into these worlds and build these relationships and build friendships with the people that we were filming with,” Kershaw says. “It allowed us to see a world that very few other people have really been a part of.”

Luca Guadagnino also got involved — the director owns a truffle dog and land in the area, and he came on as executive producer and helped advise on festivals and distribution, as well as giving notes on the edit.

The co-directors, who also shot the film, spent time looking at Italian master painters and waited until the situations and lighting were exactly what they wanted before filming, which resulted in just one shot a day, sometimes none.

“We just set the camera up and we just let it roll for one or two hours,” says Dweck, who admits that the approach presented a challenge when it came to editing. “We had no coverage.”

Sound design also played a major role in immersing the viewer into their world, says Dweck, “Sounds like every hinge on every door, what footsteps sounded like on all different materials. We had microphones on dogs, on their noses and on their paws, little mini-microphones.”

Shooting in single frames for many of the interior scenes resulted in just 107 shots in the film, which gave the page-turning effect they were looking for. “We want it to feel like you’re flipping through a storybook. Each frame is a new page in the story. If you were to watch this film with the volume turned off, and without subtitles, you would still understand the story,” says Kershaw.

Getting the canine perspective of tramping through the leafy forest wasn’t easy to achieve.

“We wanted the audience to come to understand how they react in the forest, which was quite different to the way the hunters act in the forest, and also to understand the unique relationship that they share as companions,” says Dweck. They tried several different rigs to fit a camera on a dog, but nothing worked. Finally, the cobbler who lived downstairs from the apartment in Alba where the filmmakers were staying was able to work with a metalsmith to construct a leather and metal contraption that stayed on the dog while they ran through the woods.

But getting dogs to film themselves as they hunt down truffles wasn’t the only challenge. The truffle hunters are mostly in their eighties, but they’re used to navigating rough terrain, sometimes in the dark with no flashlights.

“Carlo, for example, he says he’s faster than the deer. And he really is. We were chasing after them through woods that they know very well in the middle of the night,” says Kershaw. “There was a real physicality to all the shooting.”

The hunters are confronting droughts, agricultural run-off and profit-driven competitors that make it harder than ever before to find the extremely delicate fungi. “Carlo, he talked about when he was a kid, he would follow his father as he was plowing the fields and truffles would pop up like potatoes,” Kershaw says.

The men live such simple, almost primitive lives, yet their truffles sell for thousands of dollars to restaurants in Tokyo, Paris and Moscow. “It can last maybe a week and it sells for as much as gold,” Kershaw marvels.

The men are intensely secretive about their hunting locations, because for some younger hunters, it’s only about money, not tradition. “There’s some people that don’t respect the land. They just dig holes and pick out a truffle, that’s not right. Then it won’t come back again because the spores are then dead,” says Dweck.

Kershaw and Dweck were so moved by the threats to the centuries-old practice that they started a conservation program to fund the acquisition of land in the area, along with an educational component to bring kids into the forest with the truffle hunters and dogs and teach them about the land and the proper way to hunt.

It all comes back to their reverence for places with a local identity and a connection to nature.

“That’s why we felt there was an urgency to making this film and making it now, because when they go, we hope that this knowledge is going to be transmitted to the younger generations,” says Kershaw.