The secret searchers: the truffle hunters of Piedmont

The New European

02/09/2021

Back

By Jason Solomons

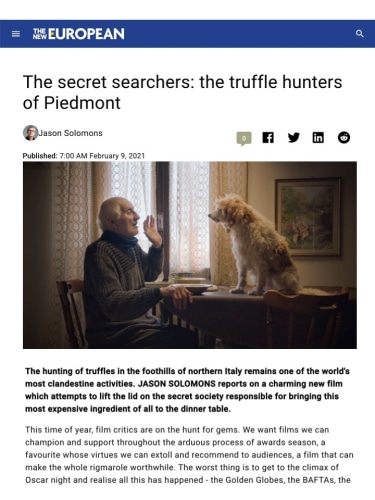

The hunting of truffles in the foothills of northern Italy remains one of the world's most clandestine activities. JASON SOLOMONS reports on a charming new film which attempts to lift the lid on the secret society responsible for bringing this most expensive ingredient of all to the dinner table.

This time of year, film critics are on the hunt for gems. We want films we can champion and support throughout the arduous process of awards season, a favourite whose virtues we can extoll and recommend to audiences, a film that can make the whole rigmarole worthwhile. The worst thing is to get to the climax of Oscar night and realise all this has happened - the Golden Globes, the BAFTAs, the European Film Awards, the SAGs, the BIFAs, the PGA and the DGA and the Cesars - and, in the end, Green Book wins.

So it is with no little relief that I present to you The Truffle Hunters.

It probably won’t win Best Picture or anything like that, but I reckon it should be top of the Documentary pile or even shine in Foreign Language film category (to be retitled at this year’s Oscars as International Feature Film). But finding this beautiful, thoughtful, charming and pungent little film has been one of the joys of the film-watching year so far.

It’s a documentary about the age-old art of truffle hunting, set near the town of Alba in Italy’s north-western Piedmont region (fly to Turin and head south) and featuring mainly octogenarian men and their dogs.

I know - I also thought you used pigs to sniff out truffles, but apparently it’s never really been the case in Italy where the famous tartufi bianchi have been tracked by dogs since Roman times. American documentary makers and photographers Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw teamed up to gain access to this arcane and secret world and the result is as charming as it is profound and complex.

Alba is, of course, famous for fungi. There are three-star Michelin restaurants, luxury hotels converted from monasteries and castles, and an annual truffle fair that attracts thousands of tourists, and a truffle auction where the elusive tubers attract thousands of dollars from restaurants around the world. But this film digs deeper to come up with something more resonant, more magical.

“It’s like a fairytale land of castles and forests,” recalls Michael Dweck of the first time he saw Alba and the Langhe hills region around it. “But it has a special feeling you can’t put your finger on and it’s that feeling I wanted to capture on film, to find out where it comes from.”

From deep in the mulchy, autumnal soil is the honest answer. It’s the same soil that gives Italy its delicate Nebbiolo grape, base for the magnificent red wines of Barolo, Barbaresco and Dolcetto and the famous white Gavi.

Adds co-director Kershaw: “The truffles are the repository of all the emotion and history of the region, all the fragility and delicate balance. These little treasures encapsulate all the magic of the world they come from and once we’d heard about the tradition of these old men who go out alone with their faithful dog every night into the woods to hunt the world’s most expensive ingredient, we were hooked.”

Taking over three years to immerse themselves in the local community, the film makers had to hunt out the titular truffle hunters and gain their trust to get them on camera. Consequently, the film plays out like an Italian thriller, with elements of Godfather-style codes and secrecy, shot with the artistic sensibility of Old Master paintings and a touch of cinematic neorealism.

For example, an old man is being lunched by a younger man who asks if he can come on a hunt with him, if he can be shown the spots where he finds his truffles. The proposition is presented carefully, matter of factly. “You have no children, no family to pass on your knowledge,” says the eager apprentice, pouring another glass of wine. “I have a dog and I can learn these things to keep the tradition alive.”

The old man looks at him. “Quello mai quello mai,” he states, firmly and finally. That will never happen, never…

Dweck laughs when he recalls setting up this scene, suspecting the 84-year-old Aurelio would baulk at the approach. “They give nothing away and would prefer to take their secrets to the grave than pass anything on to people they don’t feel respect the land or respect the dogs the way they do,” he says. “Truffle hunting is something you learn slowly - they write every single hunt down in a diary, recording the temperature, the humidity, the moisture in the soil, the phase of the moon, when and where lightning last struck. These diaries go back hundreds of years and lie deep in barns and cellars. It’s a meticulous skill and also a deeply superstitious tradition steeped in myth and they believe that it’s only through both can you find a truffle.”

The film unfolds in a series of such still, composed tableaux, the fixed gaze of the camera framing scenes that could come from Titian or Caravaggio, the farmers surrounded by old crates and barrels, farming equipment, peeling walls, seen through wooden shutters, sat at rough-hewn tables eating and talking to each other, or their dogs, always next to a large, unmarked bottle of deep red wine.

There’s another scene of another older statesman having an espresso with a younger rival. The old man was friends with the other’s father and, following some sort of feud over encroaching hunts, they’re gently discussing the rules of the truffle system, which are obviously not written down in law anywhere but demand respect and form some sort of omertà between families in this part. “It’s better to be punished by a friend than by an enemy,” suggests the rival.

Perhaps my favourite scene of all among so many is that of an old man who we’ve seen arguing at the truffle auction and the truffle fair, finally having his moment alone, in a restaurant where his order is simply two fried eggs, with slithers of truffle grated over them, washed down with a large glass of red. Caruso crackles on the soundtrack and the villainous grin on his face is a precious moment, for him and even for us, watching.

“He’s the local guy who’s been a wine taster, a chocolate taster and now he’s the truffle judge,” explained Kershaw. “Everything passes under his nose for quality control. You can’t sell a truffle in Alba without this guy and we went out for dinner with him and it was like a religious experience watching him eat and drink, so we wanted to capture that exquisite pleasure yet also his loneliness - it’s like everything else disappears while he savours the food.”

I tell the filmmakers that the film isn’t really about truffles, or about dogs, or even old men. It could be about any precious, foodie commodity with its romantic story: the acorn-fed Iberico pigs of the Spanish dehesa, the tomatina festival, Breton cider, Corsican coppa… from saffron to coffee, even to cocaine. They laugh again, because, it turns out, filming truffle trading is like being at a drug deal.

“These guys sell their truffles at 3am in the morning, in the back streets of little villages,” says Dweck. “It took a year before they’d even tell us where we could find the dealing and everything looked like it was closed and suddenly a car pulls up and the back seat opens up and this overwhelming scent of truffles filled the little square. These old guys in hats and trench coats, maybe there were 50 of them outside the little church and they descended on the car. We had no idea what was happening, where to point the camera and in minutes it was all over and they scuttled back down the alleyways, gone. All that remained was this heady perfume of truffle in the air.”

Eventually they did film some deals and negotiations, a hunter getting 500 euros for his 350 gram truffle under a street lamp. Then we see the dealer in his room, spreading his shrooms out like diamonds on a white cloth, on the phone to Paris, to a restaurant, holding out for 4,500 euros a kilo. Even famous chef Enrico Crippa, who runs Alba’s three Michelin starred Piazza Duomo, often voted among the top 15 restaurants in the world, gets his truffles in the Piedmont backstreets at 3am.

Out in the forests, the film makers capture the dense undergrowth and the crackle of twigs, following the men and their dogs. Using a specially constructed dog-cam (“a local shoe cobbler invented the rig for us while we waited”) we get all the excitement of a ‘find’ and also get let into the almost romantic relationship between hunter and dog - the hounds including Titina, Birba and Fiona get their own star billing in the film’s credits - but it feels to me like a study of man’s relationship to the earth and to history that makes his film so treasurable.

Dweck believes that because truffles can’t be cultivated and the hunters’ secrets are so well protected by their own adherence to tradition, the custom is not in danger. But there are surely concerns over the sustainability of such an industry, worried over declining yields and, even, I suggest, over the increase in interest this lovely film is going to spark?

“The point of the film is to protect this way of life, this eco-system,” he says. “It is lessening due to climate change and agricultural changes such as deforestation to make way for more Nebbiolo grape vines but we want to make sure the land is protected.” The film makers have set up a non-profit conservation project in Langhe to protect the land as demand increased from Russia, China and America.

There is already a thriving tourist industry around the truffles. Dweck recounts how he went on a tourist truffle hunt and the mushrooms were clearly planted to make people feel they’d got lucky but that the real thing is a vastly different experience. Will they tell the secret spots they found?

Quick as a flash, Michael and Gregory protest: “We don’t even know where we went!”

“Honestly,” says Kershaw. “After we eventually persuaded them to take us out one night and let us put the cameras on their dogs, they stuck us in the back of a truck and it was pitch dark and we drove around for hours into these valleys and into deep woods. We had no idea where we were and certainly no clue as to how to get back there.”

An abiding image is of a prize truffle at auction, sitting on a plump velvet cushion, ceremonially positioned like a monarch and carried in by beautiful local women. It fetches nearly 100,000 dollars. What do you do with it, I wonder?

Dweck says he has learned there are only three proper ways: shaved over eggs (fried, baked or scrambled); shaved over local ‘tajarin’ (sometimes taglierini or tagliolini) pasta tossed in butter and little of the pasta cooking water; or shaved over a risotto of the local castelmagno cheese.

So, yes, it’s about dogs and old men and quaint Italy and village life, but it’s really a film about economy and food, about history and tradition, about human nature and the pursuit of the precious, about pleasure and connection to the earth and, in certain moments of stillness and bliss, the little secrets about what really matters in life.

“It’s also about time,” concedes Kershaw. “The truffle, this stuff that’s worth thousands of euros, supports a whole region and a way of life - but you have to eat it within three days of it being unearthed. So, yes, the whole world of the film is wrapped up in the experience of eating the truffle.” Is it worth the fuss, I ask?

“Anyone biting into it is accessing a whole tradition, the ritual of the hunt and the story of it that goes back centuries,” says Dweck. “That’s all somehow transferred to those consuming it and paying these huge amounts of money for it. You’re really buying a piece of magic, I think.”

The Truffle Hunters will be released in cinemas when restrictions allow; it will also be available on streaming platforms from February 5

TRUFFLE TIMELINE

The region's white truffle became renowned across the continent by the 18th century. Truffle hunting became a form of court entertainment, with foreign ambassadors based in Turin invited to take part. This may be why dogs came to be used, rather than pigs, as was the custom in France.

Local rulers Vittorio Amedeo II and Carlo Emanuele III were considered particularly dedicated hunters. The Piedmontese politician Count Camillo Benso di Cavour - one of the architects of Italian unification - even pioneered a form of truffle diplomacy, sharing the delicacy with those he wished to flatter and persuade.

The composer Gioacchino Rossini called it “the Mozart of fungi” while Lord Byron kept one on his desk because the smell helped to inspire him. Alexandre Dumas appears to have been a particular fan, with several quotes on the subject of the delicacy attributed to him, among them that they "make women more tender and men more lovable", that “to tell the story of the truffle is to tell the history of world civilisation” and that they were the "Sancta Sanctorum" of the dining table.