The man who got America hooked on lattes bankrolled a documentary on a stock-car racetrack

Market Watch

02/05/2018

Back

By Tom Teodorczuk

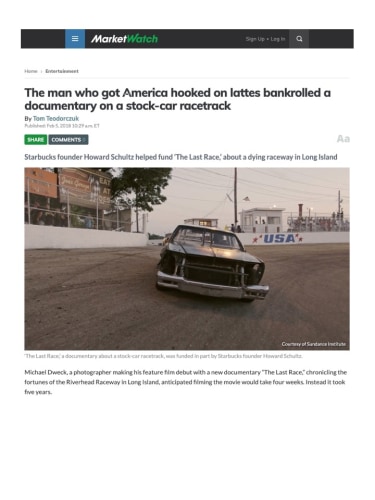

Starbucks founder Howard Schultz helped fund ‘The Last Race,’ about a dying raceway in Long Island

Michael Dweck, a photographer making his feature film debut with a new documentary “The Last Race,” chronicling the fortunes of the Riverhead Raceway in Long Island, anticipated filming the movie would take four weeks. Instead it took five years.

“It took a month just to put a camera inside a driver’s face,” Dweck told MarketWatch at the Sundance Film Festival, where the “The Last Race” had its world premiere. “I had to build up trust. We put a lot of money and time in it.”

With the long shooting schedule and post-production occurring in Scandinavia, the doc ended up costing $500,000. A white knight emerged in the form of Starbucks SBUX, +0.59% founder and executive chairman Howard Schultz, who contributed to the movie’s budget and, along with his wife Sheri Schultz, is a co-executive producer.

“Howard is a collector of my fine art photographic work, and so when I was running out of money — because I was putting all of it into the film — he gave me one-fifth of the film’s budget,” Dweck said. “It was a super nice gesture — he gave it to me without asking any questions.”

“The Last Race” visually depicts life at the Riverhead Raceway track during the final years of its ownership by the octogenarian couple Barbara and Jim Cromarty. One of the oldest stock car racetracks in the country, having been built in 1949, Riverhead Raceway is the only NASCAR stock car track in the New York metropolitan area.

In addition to footage of stock car races, with cameras situated inside the cars and microphones in the tailpipes and the drivers’ helmets, Dweck’s documentary shows the Cromartys resisting offers of up to $10 million from developers bidding to transform the race track into a retail park.

“When the racetracks were built they were typically in rural areas, where there was no development, but the land has become so valuable, it doesn’t pay to have a racetrack any more,” said Dweck.

“Barbara and Jim are wealthy, they’ve been doing this long enough and didn’t need the money. But every day I was filming them there would be a knock on the door from a developer saying they wanted to buy the track. They would say, “Get out!””

The Cromartys, both suffering from ill health, ultimately sold the racetrack to trucking company owner Eddie Partridge in 2015 for a reported $4 million. They had owned Riverhead since 1985 and had been running it since 1977.

“They made a decision to hold off to the very last minute and ended up selling the track for relatively next to nothing to keep it open with the agreement that the new buyer would keep it open, but that wasn’t in writing,” Dweck said.

Although “The Last Race” isn’t a polemical work, Dweck,a former advertising executive who became the first living photographer to have an exhibition at Sotheby’s US:BID auction house in 2003, laments the decline of amateur auto-racing tracks in the U.S.

“It’s 100% Americana and there’s very little left of it,” he said. “Americana to me is your identity being tied to a place. With these types of racetracks, the drivers identify with this place, the owners identify with this place, the fans identify with this place.”

“It’s a piece of dirt and yet the identity of thousands of people are tied to this inanimate object. Without the cars it’s a parking lot that you can build around. You see how vulnerable it is.” He lamented the opening of a Wal-Mart store WMT, +0.06% next to the Riverhead Raceway in 2014.

New York’s Long Island was a haven for auto-racing tracks in the 20th century, but Riverhead Raceway is the last venue standing. One scene in the movie depicts real estate developer Marty Berger outlining the inevitability of Riverhead making way for a shopping mall, as he is playing golf.

Dweck said: “While playing golf, surrounded by trees, he’s presuming that what the 2,000 people that have been coming to the place since 1949 — in some cases third generation families — really want is to buy more crap like chicken wings and Christmas tree ornaments. That’s what developers do!”

In addition to economic pressures, Dweck ascribed the decline in amateur auto-racing to computer games. “The younger generation is consumed with technology,” he said. “Do they want to work all night on a car in a garage with their father and get their hands greasy or do they want to play video games? They play video games and get fat.”

Dweck said that the new owners of Riverhead had modernized the track which, as part of the NASCAR Whelen All-American Series circuit, runs several divisions each weekend of operation. “They knocked down the wooden structures that had been there since the 1940s as they thought people wanted more modern things at the racetrack, which I don’t agree with, as I thought it was part of the charm.”

“It was a time capsule, for instance their aluminium speakers are from the 1964 New York World’s Fair. I don’t know anything like it, at least not in the New York area.”

“The Last Race” was voted one of the top five documentaries at Sundance in a poll conducted by the movie website IndieWire and has been tipped to be picked up for release by a streaming service.

Dweck added that NASCAR had supported the documentary, though unlike Schultz, auto-racing’s sanctioning body hadn’t given it financial backing: “They have told us it was the grass roots of where they started — the DNA of NASCAR — and they want to preserve it.”