The Festival! NYFF 2020

Bright Wall/Dark Room

10/27/2020

Back

By Fran Hoepfner

The New York Film Festivals Of The Past

I live in New Jersey, though by the publication of this essay, I won’t live in New Jersey anymore. This doesn’t matter, other than to say that in past years of covering the New York Film Festival—NYFF, let’s be casual, we’re on the third date—I would wake up early then cross state lines to watch a movie. I did this all the time. I saw movies in New Jersey sometimes: in fact, the last movie I saw in theaters this year (The Way Back, obviously), I saw mere blocks away from my house.

Don’t get me wrong: I loved crossing state lines to cover NYFF. Early in the morning, I would drift through the still-empty streets of my neighborhood, and hop on two under-crowded trains all the way up to Lincoln Center. I am human, which is to say I love When Harry Met Sally and I love Moonstruck, and so if there is a time in which Lincoln Center will lose its appeal to me, I have no idea when it is. All of which is to say, I yearn for the early morning lines, the smell of coffee, the plush seating, the eager chatter. I miss seeing my friends. I miss making friends! But I have continued to watch movies because I love them, and when it is safe for me to return—to Lincoln Center, to a multiplex, to one of the arthouse places where I always run into someone I don’t want to see—I’ll be there.

The New York Film Festivals Of The Present

I, like many children of the 1990s, grew up with the scene from Matilda in which Mrs. Trunchbull makes that poor boy eat all the chocolate cake playing on repeat, both as fantasy and omen, inside my little skull. As someone who fell in love with movies at a time when most were consumed only somewhat legally and watched on my laptop in bed, I must quote critic Bilge Ebiri and say, “When this thing is over, if anyone ever catches me watching another movie on a laptop, they have orders to shoot on sight.”

I have a television and all of the requisite cords to connect my laptop to my television, but even a 50-50 split of TV-to-laptop viewing for this year’s NYFF was, if I may be so bold to say, not the same. I am grateful, always, always, to be able to watch films for a partial living, but there was a unique bummer to the viewing of this year’s festival films at home. Part of what is glorious about the movie-going experience is that you surrender yourself to what is happening. No such luck at home. No such luck in times of strife. I would give a limb—not my dominant one—to be able to sit through all three hours of Malmkrog in the Walter Reade theater, eyes burning from all those minutes spent reading subtitles.

Something Vague On The State Of Movies Nowaday

I got an MFA in fiction writing, which is how you know I am qualified to say something about the movie industry, but I sort of think—and please, do not yell at me, we’re all very fragile right now and I mean this with the utmost compassion and complete lack of understanding of how finances work, again, an MFA—this is a good time to expand coverage, expand accreditation, expand viewing. In the way that I believe that everyone should just have free money (I’m told by those smarter than I that this is called “universal basic income”), in a year like this, just let people engage with art with a much lower barrier to entry. Like I said, don’t yell at me.

Malmkrog

I have, at this point in my writing career, earned a fair amount of derision for comparing every piece of art I engage with to grad school, but I’m serious this time, hear me out: Malmkrog is about grad school. Cristi Puiu’s frigid (literally) three-plus hour living room drama is a textbook come to life. Set in an ornate Transylvanian manor, a group of six people discuss war and God and politics and culture and the Devil and so on and so forth. Like an hour into the movie, one of them suggests they table the conversation until later, only to decide against doing it. In the way that the modern era has exposed the fakeness of several dozen systems, to watch these people argue and debate as the world around them shifts and turns is as apt a portrayal as any I’ve seen. For all of my wry joking about this being the quintessential festival film (long, European), Malmkrog is likely the most prescient of the films I watched—even if I didn’t much care for it.

The Documentaries

Occasionally when I spoke to people about the best film of 2020—Kelly Reichardt’s First Cow, of course—they pushed back against the claim that it is tender. No, they’d argue, it’s heartrending. It’s brutal. There is kindness in the film, but it is not a film about kindness. One of the most wonderful and horrible parts of humanity is that not everyone you meet will agree with you.

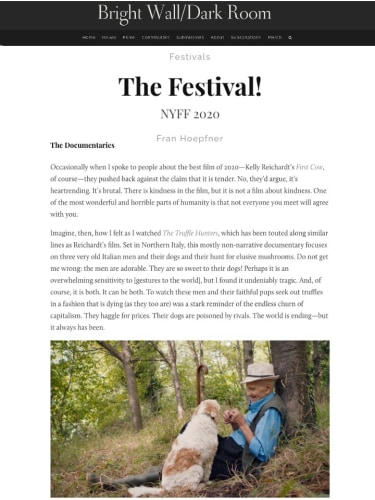

Imagine, then, how I felt as I watched The Truffle Hunters, which has been touted along similar lines as Reichardt’s film. Set in Northern Italy, this mostly non-narrative documentary focuses on three very old Italian men and their dogs and their hunt for elusive mushrooms. Do not get me wrong: the men are adorable. They are so sweet to their dogs! Perhaps it is an overwhelming sensitivity to [gestures to the world], but I found it undeniably tragic. And, of course, it is both. It can be both. To watch these men and their faithful pups seek out truffles in a fashion that is dying (as they too are) was a stark reminder of the endless churn of capitalism. They haggle for prices. Their dogs are poisoned by rivals. The world is ending—but it always has been.

Though I’m partial to the sentimentality of The Truffle Hunters, I was lucky to watch two more sobering documentaries at the festival this year: Sam Pollard’s MLK/FBI and Jia Zhangke’s Swimming Out Till The Sea Turns Blue. MLK/FBI is a tapestry of archival footage, cleverly constructed and enduringly necessary. Though commemorated as a hero now, an often-ignored part of Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy was the U.S. government’s disdain and distrust of him. Swimming Out Till The Sea Turns Blue is told in a series of interviews with aging writers from the Shanxi province. In many ways, it bears resemblance to The Truffle Hunters—a sobering look at both then and now—with brief poetic interstitials. It’s perhaps the type of documentary that appeals to more of a self-selecting audience, but I found its interview footage compassionate and intriguing, the stories worth hearing.

The McQueens

Steve McQueen is back! It is my understanding that writing and producing and directing films takes up time, but it sure feels like a whole millennia has passed since Widows. I’ve long admired McQueen and his artful approach to misery and injustice and suffering. If there is a type of person who is prone to saying “Fuck it, I’m going to rewatch Shame,” I am that person.

His new project, Small Axe, is an anthology series of films—not TV!—that will debut on Amazon later this year. Through NYFF, I was lucky enough to be able to watch three of them. Though they’re not interconnected narratively, the films are united around London’s West Indian community. Mangrove is a sturdy procedural, full of wonderful performances including an electric Letitia Wright. It tells the true story of a man named Frank Crichlow, the owner of the Mangrove café who was arrested for protesting police brutality. It’s certainly not the only social justice-oriented legal procedural you’ll watch this fall, but I’d argue it’s the stronger of the two, with much less inclination to sentimentalize. It errs on the side of clunky in its dialogue (an even worse issue in Red, White and Blue) but like so many courtroom dramas, once they’re in court, we’re good to go.

Red, White and Blue, however, despite featuring an always good John Boyega, is irritatingly on the nose. It tells the story of Leroy Logan, a Black police officer eager to change the system from the inside. I’m sure…you can guess…what the result of trying to reform the police from the inside looks like, right? Boyega’s Logan is tough to read: it’s not really all that apparent why he wants this. Steve Toussaint, who plays Logan’s father Kenneth, is the much more richly embodied character. Disappointed, frustrated, worried for his son’s wellbeing and undeniably frustrated with the behavior of the police. Perhaps this would have been the character to focus on? I’m not able to say more, not out of fear of spoilers, but because I found this to be the type of filmmaking in which there is little else to say. It’s all on its face, for better or worse.

Where I could write an opus, however, is Lovers Rock! (Exclamation point my own.) Here is a balm, here is a bop. McQueen tips into a register I’ve rarely seen from him: joy. Set at a house party, Lovers Rock is a glowing, impassioned ode to Black joy. Lovers Rock! A swelling, wonderful party. Maybe features the needle drop of the year? Lovers Rock! When the screeners were re-released to those of us in press and industry, I rewatched this one in full. I had to. I couldn’t wait until December. My body wants to dance. I am an extrovert who likes to go to bed early, but it made me miss the chaotic exuberance of a party. My heart swoons just thinking about it. I wonder what it will be like to hold someone’s hand again.

I don’t even know what a traditional narrative looks like anymore

One of the reasons why a film like Lovers Rock struck such a nerve is that it’s largely non-narrative. Over a sleepy, long, hot summer, other writers and I discussed whether or not the narrative arc still mattered, or if a year like this one had rendered it useless. That’s not to discount growth or its queasy opposite, but I see why it’s more a question than it was in the past. Two films—I Carry You With Me and The Disciple—while both about undeniably interesting subjects, hewed too traditional in their structure. The former, Heidi Ewing’s romantic docudrama, is evocative and swoony when it gives itself over to the flirtations of its protagonists. Though the film has plenty to say about gay love in Mexico and the opportunity of change in immigration, the narrative is too bogged down in flashbacks. I almost never need to know about someone’s childhood! The Disciple, directed by Chaitanya Tamhane, is the portrait of a young man in India striving to become a great Hindustani classical musician and singer. The music is wonderful and the discussion of craft is more than engaging. I doubt there’s a music movie like this one—and the world of the plateauing artist is often underrepresented in film. But there was something oddly conventional about it—slightly rote and exhausting. Perhaps that’s the nature of a skill: tedium.

There were other films, however, that bucked the notion of traditional narrative for something more obscure and original. The Woman Who Ran, Hong Sangsoo’s latest collaboration with Kim Min-hee (always great!), is a three-part look into a woman spending time away from her husband. She catches up with old friends. There’s some drama with neighborhood cats. Did she leave her husband? Or are we supposed to presume this to be an otherwise normal departure? The film, though short, is sleepy and largely uneventful. To quote a friend, “I’m waiting for this to tell me what the point is.” I have been trying to make headway of it as well; maybe it’s that absence is not all that uneventful. That we know how to fill space better than we think. Sometimes to run is to walk.

The Human Voice, Pedro Almodóvar’s film short with Tilda Swinton, was a little substance-less for my liking, but it looks amazing. And hey, as more time passes, even the mere concept of Tilda Swinton in Airpods delivering a mid-breakup monologue sounds better than it was. In the coming years, I think we will see a lot of films—long and short—that feel experimental, enclosed. The Human Voice was produced and shot in a post-COVID world: its containedness is a part of its appeal. I could hardly bring myself to invest, emotionally or otherwise, despite it being the exact type of thing I know we’re about to see a lot of.

Philippe Lacôte’s strange and dreamlike Night Of The Kings was a wonderful addition to the festival this year, a retelling of One Thousand and One Nights in which a new prisoner in a prison in Abidjan must keep his fellow inmates and self-appointed king entertained for a night. The film mixes engaging storytelling—complete with interpretative movement and dance—with effects-heavy world-building. The former works better than the latter, but the film is a prime example of a simple premise and adaptation executed originally.

What I wanted from the festival this year was stuff that was weird––we do live in weird times, after all.

Christian Petzold Corner

Am I becoming an unstoppable Christian Petzold fan or am I in love with Franz Rogowski? At this point, it’s impossible to say. Petzold’s last movie, Transit, was a sleepy, romantic mindfuck. It took place both out of time and very much in time. The same can be said of his new film, Undine, which reunites Transit’s Rogowski and Paula Beer, in a meditation on architecture and memory and loves lost and found. It may be a tough film to parse for those unfamiliar with Petzold’s work up until this point, but maybe not! Romance transcends ambiguity, right? Rogowski’s Christoph and Beer’s titular Undine have the most memorable meet-cute in a minute: accidentally bumping into a precariously placed fish tank that cracks, its contents gushing out and on top of them.

Their romance has that heaving, absorbing energy to it. BW/DR’s own Veronica Fitzpatrick shared a still I haven’t been able to shake. If love teaches us to clutch onto one another for dear life, what does it mean when that tether breaks? Are we able to float on—or do we sink to the depths of another’s despair? Unlike Transit, where I sat in a state of disoriented admiration for its entirety then fell hard for it in its final act, I felt a little lost with where Petzold leaves Undine. There’s such deliberate peculiarity in his brand of ambiguity that I don’t mind it much. It only gives me an opportunity to return soon enough.

No

I did not like French Exit at all, though it is always a delight to see Michelle Pfeiffer on screens both large and small.

Frances x Frances

I may have been cooler on Nomadland than many of my peers, but in the weeks since watching, what stays with me is Frances McDormand’s ability to actively listen on screen. So much of Chloé Zhao’s latest feature is about the act of bearing witness: not just the audience to McDormand’s Fern but Fern to her fellow nomadic people, to her fellow temporary coworkers, to the ever-shifting country around her.

When being dismissive and curt during our troubled times, I have said that the pandemic really separated the adults from the babies. This is a coping mechanism, no doubt: I have not had the luxury—financially or otherwise—to opt out of my own life. I have slogged and churned with the sway of things. I have spent months waiting for unemployment money. I have known the value of a dollar. But to me, Nomadland is less about the economy and more about the unbearable loneliness of aging. The shape of the world right now has made clear the precariousness of life, something otherwise pushed aside for something glitzier or marketable. What is so admirable about Nomadland, and specifically McDormand in Nomadland, is that it lays out the isolation and exhaustion of being pushed out of one’s own life. Once you’ve gone so far out of the world of the living, but more importantly the world of the spending, is it possible to come back? I don’t know. I don’t know if any of us will know for a while.

In summation

The movies are still here, and so are a lot of us. If I sound like a grouch it’s because I am. It’s been a good year to be a grouch. Even so, know that with every tap of a space bar, every click of the play button, I lean back and wait and hope and anticipate something new, something great.