The Charming Documentary Where Truffle-Hunting Dogs Are The Stars

Huff Post

03/05/2021

Back

Directors Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw embedded themselves among enigmatic Italian practitioners to make “The Truffle Hunters.”

By Matthew Jacobs

When Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw decided to make a documentary about the secretive world of Italian truffles, they asked a local trattoria owner to introduce them to the restaurant’s supplier. Only then did Dweck and Kershaw realize what they’d gotten themselves into. “He said, ‘Oh, I’ve never met the guy,’” Kershaw recalled. “‘Every night I put the money in a box outside the door. The next morning, there’s a truffle.’”

These gastronomic excavators — at least the ones in Northern Italy’s Piedmont hills, where “The Truffle Hunters” takes place — are a rarified bunch: aging technophobes who deploy their well-trained dogs to sniff out and unearth small fungi that can sell for thousands of dollars per kilo. Many of them have done this their whole lives. Now they face a business threatened by climate change and over-commercialization, hence their stealth. Some dealers prefer to make transactions in the dead of night, cloaked by relative anonymity.

Dweck and Kershaw spent upwards of three months acquainting themselves with the region and its practitioners before shooting any footage. They’d meet someone at a trattoria, for example, who would introduce them to a cousin who knew someone who knew someone who was a truffle hunter. The next challenge came in making that person feel comfortable enough to allow cameras. Unsure exactly what the resulting movie would entail, Dweck and Kershaw — both American — traveled with a translator who was so critical to the process they gave her a producer credit. It took them three years to finish the film, which has been shortlisted for the Oscars’ Best Documentary Feature category. (It is now playing in select theaters and will premiere on video-on-demand platforms this spring. Luca Guadagnino, the director of “Call Me by Your Name” and “We Are Who We Are,” is also a producer.)

“We wanted to understand the world of the people that we were filming,” Kershaw said during a recent phone conversation. “We wanted to understand the web of relationships that surrounded them. We wanted to be able to just experience the world and feel it deeply and look at it from all sorts of different angles — and maybe find moments of beauty or peculiarity, things that maybe you would miss on first glance, but by spending a lot of time, you discovered. We became friends with them. We shared a lot of meals. We talked about our lives. We talked about why we wanted to make this film, why we thought their lives were so important, why we thought their lives were so full of wisdom.”

Because of its picturesque setting, “The Truffle Hunters” has an elegance that most vérité documentaries can’t match. It looks like a series of paintings. Dweck and Kershaw don’t use talking-head interviews or history lessons to steer the narrative, instead chronicling the specific customs of five hunters and their precious pooches.

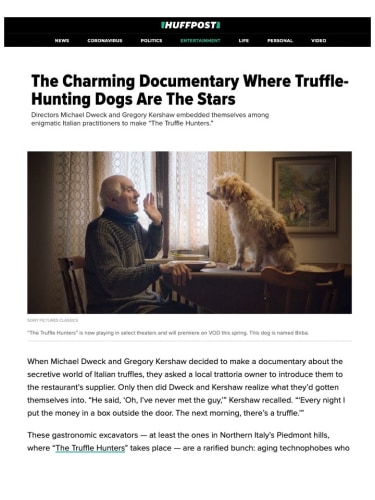

There’s 84-year-old Aurelio, who is concerned about what will happen to his sweet hound Birba when he dies. And Carlo, a jaunty 88-year-old known for sneaking out of his window at night to go hunting with Titina against his wife’s wishes. The most idiosyncratic of them is Angelo, a disenchanted poet who quit because rival hunters started planting poison to kill the dogs. He once threatened someone with a machete, Kershaw said. It took the directors two years and a lot of Gorgonzola to convince him to participate.

“It was like this constant dance to try to be in these places where they could be unencumbered in front of the camera and we could just sit there and really watch,” Dweck said. “Once they felt like we were part of their family, only then did we take the camera out. We saw this world as a fairy tale, and we wanted to take the audience through, painting by painting by painting.”

Following the men’s adventures — it’s always men; the region’s women have their own secrets, Dweck promised — feels like entering a storybook. A community untouched by cell phones, Wi-Fi and other markers of modernity, the subjects in “The Truffle Hunters” might as well be living in the 1950s. But they aren’t merely stuck in the past; they remain connected to nature in a way that many of the planet’s inhabitants don’t. Their soulfulness is aspirational.

Dweck and Kershaw shot at least two hours of footage for every minute we see in the finished film, using natural light to accentuate the overwhelming majesty. Eventually, the directors accompanied their new friends to doctor’s appointments, haircuts, lunches and the intense exhibitions where prized truffles are marketed. Along the way, they would share what they’d recorded, ensuring everyone understood the documentary’s aims. Elsewhere, Dweck and Kershaw attached GoPros to the dogs as they sped through forests to dig up morsels.

Truffles originated as a European luxury. The sought-after Alba white variation grows near the roots of oak trees and depends on fertile environmental conditions. Finding them is “like finding gold,” Kershaw said. American farmers have started to cultivate their own crops in recent years. They, too, utilize dogs for the grunt work. In Oregon, the Truffle Dog Company offers training and consultation. But it’s a lot harder — and quite expensive — to grow the product by hand. An industrial engineer profiled in The Wall Street Journal in 2017 said she’d spent $500,000 to plant 24 acres’ worth. But even as domestic truffle enterprises expand, they lack the organic joys of the Italian experience.

“The Truffle Hunters” is an enchanting portrait of stalwarts who have maintained the lives they want to lead, even as society has moved on. Their dogs steal the show — especially Birba, who might as well be a Pixar character — but the film is a charming and poignant testament to humanity. It speaks to the mythology of the truffle itself: Some hunters believe the delicacy grows according to lightning patterns or phases of the moon; others call it witchcraft. All agree it’s an ideal way to bond with a pet.

“We needed to make this film because it possessed a beauty and a magic,” Kershaw said. “It possessed a mystery that just seemed bigger than real life to us. The people that we were encountering, they seemed bigger than life. Our hope is that it reflects back to the audience and they feel that. It should take you to another place. It should be filled with a kind of magic that doesn’t feel like it’s part of this world, because that’s what this place was.”