Sundance Review: Gaucho Gaucho is a Stunningly Beautiful Chronicle of Community

The Film Stage

01/30/2024

Back

By Jose Solís

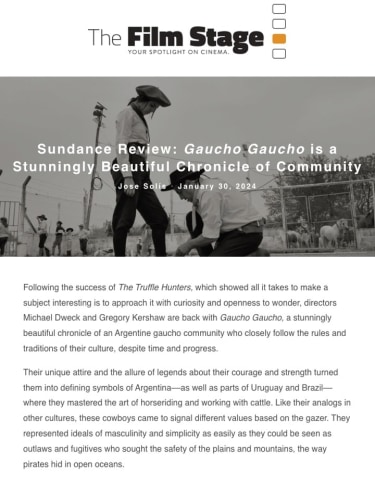

Following the success of The Truffle Hunters, which showed all it takes to make a subject interesting is to approach it with curiosity and openness to wonder, directors Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw are back with Gaucho Gaucho, a stunningly beautiful chronicle of an Argentine gaucho community who closely follow the rules and traditions of their culture, despite time and progress.

Their unique attire and the allure of legends about their courage and strength turned them into defining symbols of Argentina––as well as parts of Uruguay and Brazil––where they mastered the art of horseriding and working with cattle. Like their analogs in other cultures, these cowboys came to signal different values based on the gazer. They represented ideals of masculinity and simplicity as easily as they could be seen as outlaws and fugitives who sought the safety of the plains and mountains, the way pirates hid in open oceans.

Approaching their new subjects with utmost respect and curiosity, Dweck and Kershaw eschew any context or impose any meaning, diving directly into the world they’ve been allowed to visit. We’re presented with a limited set of characters they follow and capture through different events and moments. Interspersed without the need to create dramatic tension, they cut back and forth between them, creating a harmonious work that feels like we’re seeing daguerreotypes come to life.

The black-and-white cinematography brings out unexpected beauty and contributes to the sense that we’re watching timeless figures––ghosts, even. Because these ghosts remain within the confines of their culture by choice, they interact with modern beings in a limited way. A gaucho hat on a head stands out almost comically in the middle of a school classroom; it’s even more surprising to discover it’s not a boy but a girl, Guada, who listens attentively to her teacher’s reminder that she is supposed to wear her uniform to school. The girl replies she is a gaucho and feels more comfortable in her traditional attire. Throughout the film we learn Guada is also defying the norm at home by taking part in traditions usually reserved for men.

Other “storylines” include a conversation between a priest and a gaucho who is invited to think about his legacy and how he wants to be remembered; this makes for a touching contrast with Lelo, a gaucho in his 80s who looks back at life without regret. A thematic thread between the stories and characters is a sense of languidness and being in the present, which strangely adds to the film’s atemporal mood.

We know that gaucho culture isn’t widespread, but the film never makes us feel we’re watching something on the verge of disappearing. There is an underlying sense that a culture like this can never disappear. A man comments on the ominous condors circling above them and explains they can fly down at any moment and attack defenseless prey; but he delivers this piece of wisdom without any signs of fear, as if the condor knows better than to mess with a gaucho.

One of the loveliest tracks follows Solano and his toddler son Jony, who follows his dad around, absorbing every piece of gaucho knowledge he can. The father looks attentively as his son learns how to sharpen a knife, his eyes filled with pride and the slight fear the boy might hurt himself. This effortless passing down of knowledge from generation to generation infuses the documentary with unexpected warmth. Watching Solano and Jony walking toward the horizon doesn’t have the melancholy found in films like Shane. Instead, it feels present and alive.

The filmmakers leave the gaucho community the same way they arrived, a tracking shot that turns the camera into a train that stopped briefly in a place we otherwise wouldn’t know existed, each viewer taking a custom souvenir. For some a lesson in courage and tenacity or curiosity about how this culture came to be; for others, it may be simply the snapshot from a trip they won’t regret taking.

Gaucho Gaucho premiered at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival.

Grade: B+