SUNDANCE 2018: THE LAST RACE, ON HER SHOULDERS

Roger Ebert

01/23/2018

Back

By Nick Allen

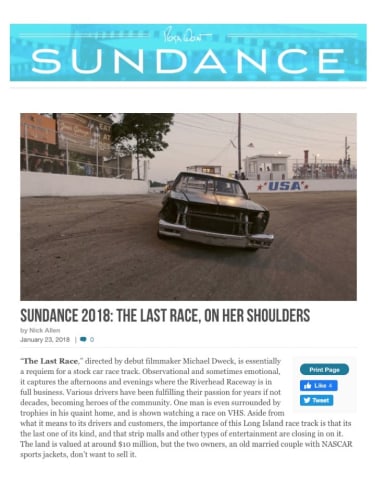

“The Last Race,” directed by debut filmmaker Michael Dweck, is essentially a requiem for a stock car race track. Observational and sometimes emotional, it captures the afternoons and evenings where the Riverhead Raceway is in full business. Various drivers have been fulfilling their passion for years if not decades, becoming heroes of the community. One man is even surrounded by trophies in his quaint home, and is shown watching a race on VHS. Aside from what it means to its drivers and customers, the importance of this Long Island race track is that its the last one of its kind, and that strip malls and other types of entertainment are closing in on it. The land is valued at around $10 million, but the two owners, an old married couple with NASCAR sports jackets, don’t want to sell it.

With a distinct eye, “The Last Race” touches upon different feelings that come from the racing hobby, whether it’s tearful pride for winning or snarling aggression towards getting hit, and creates an emotional essay that wants to document passion. This place, and its inhabitants, are various nutshells of Americana, testosterone and nostalgia, as captured through sporadic interviews and numerous observational passages of their lives in and out of the race track. But the movie is very much a lament, coming first and foremost from an outsider, especially with the classical music cues (indeed, Mozart’s “Dies Irae” from his Requiem appears to tie together the film’s sentiment). Though its cameras are unobtrusively embedded in the atmosphere, it’s not the type of movie that would be shown at the race track, to give you an idea.

Still, there is an accomplishment and ambition in the different ways that Dweck is able to film a sport that consists of vehicles going in circles. We get gripping views from inside a car looking at a driver, or on the back bumper as other cars follow behind and inch closer and closer, or from the spectator’s point, or from the commentator’s point, watching the entire track. With these moments often carrying on for long takes, they sometimes risk repetitive emotional notes, however intentional, to show the importance this sport has to so many different people. “The Last Race” captivates enough with its quiet moments, but its lyricism struggles to say much that is new or impactful.

Meet Nadia Murad. She has a story to tell in "On Her Shoulders"—Nadia is the survivor of the genocide of the Yazidi people in Iraq that killed 700 people, escaped sexual slavery from Isis, and is now trying to get people in power to actively care about those who have been killed, are still enslaved by ISIS, or are in refugee camps without a sense of home. As much as Nadia wants to be more than her story, to enjoy life as it is, she must revisit the trauma for the sake of other people’s experiences, and to be heard by various government officials so that they officially recognize the genocide of the Yazidi people. As she states, she speaks for “millions without a voice.”

We watch Nadia in various interviews and meetings, and in a low-key narrative arc, prepare a speech to become appointed as a Goodwill ambassador for the United Nations, later with the help of Amal Clooney herself. Throughout, we see the wear this has on Nadia, and yet she must keep going through each interview, each tearful speech. Director Alexandria Bombach takes a more experiential approach to sharing this life, documenting what Nadia thinks and feels as a representative of her people, and a traumatized messenger. It makes for an often fascinating but heartbreaking portrait of larger issues: trauma, the best way to be an ally to those who have been traumatized, and our cultural need to hear awful accounts in full detail before we do something about them.

There is a gorgeous ambition to Bombach's project, of getting out Nadia’s message by sharing her headspace, while humanizing her in a way that clips on tearful radio interviews do not. This is done beautifully in a few ways, like when observing her in different interview moments where she is quiet, and her partner/translator Murad relays horrifying questions that interviewees feel they must ask to get some sort of concrete picture. There are other passages too, as when people try to figure out the best way to talk to Nadia, aside from expressing de facto sympathy. Everyone knows that what she has experienced is horrible, but as mere listeners to her, so many people are unsure of what they can do. The best passage is when Nadia is shown sitting down for a radio interview, one of my many in which she shares disturbing details about her pain and those of others. The audio is overlaid with those from other interviews, effectively showing the repetitive, draining nature of her cause.

To provide an up-close idea of Nadia and sometimes Murad, Bombach also effectively uses Interrotron interviews, where she speaks directly to the camera about what she has been unable to say when only asked questions; how she wanted to work with hair before everything happened, or explicitly how she wants to be more than her story. These moments alone make the documentary worthwhile, as if providing Nadia with the first type of outlet in which she can speak on in her own terms.

Emotional delicacy is a major component to this documentary, which makes all of its bolder expressions especially magnified. This works in a positive way like whenever we see Nadia steal a grin or smile at the camera, after stepping outside a dressing room or noticing random kids goofing it up for the documentary cameras following her; “On Her Shoulders” is much more than just sadness. But given this tonal balancing act, whenever the doc wants to add its own tears, as a sad string score sometimes does, it proves especially invasive. Being in the same room with Nadia says enough in the very powerful “On Her Shoulders,” even when she is alone with her thoughts.