Pure and simple: how nature documentaries became cinema’s answer to ASMR

The Guardian

07/05/2021

Back

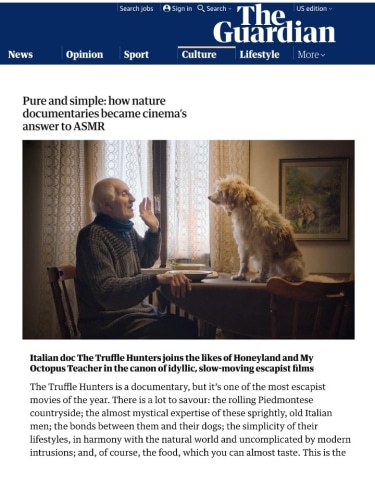

Italian doc The Truffle Hunters joins the likes of Honeyland and My Octopus Teacher in the canon of idyllic, slow-moving escapist films

By Steve Rose

The Truffle Hunters is a documentary, but it’s one of the most escapist movies of the year. There is a lot to savour: the rolling Piedmontese countryside; the almost mystical expertise of these sprightly, old Italian men; the bonds between them and their dogs; the simplicity of their lifestyles, in harmony with the natural world and uncomplicated by modern intrusions; and, of course, the food, which you can almost taste. This is the sort of lifestyle we digital-age urbanites fantasise about packing in our careers for, like Daniel Day-Lewis going off to make shoes.

CGI landscapes are now commonplace at the multiplex. Some of them, such as Pixar’s recent Luca, even seek to digitally simulate an Italian village locale similar to that of The Truffle Hunters. But it is the real rural experience many of us now crave. Calm, simple, sensuous and reassuring, it’s the cinematic equivalent of ASMR.

The Truffle Hunters has been described as “this year’s Honeyland”, in reference to the 2019 documentary centred on a wild beekeeper in remote North Macedonia (the bees are wild, not her). It ticked a lot of the same boxes in terms of pastoral splendour, patient observation and produce that would fetch a small fortune at a farmers’ market. Not to mention nostalgia for a disappearing lifestyle. Honeyland was acclaimed as one of the year’s best movies, full stop. It won Oscar nominations for not only best documentary but best international feature.

Before now, such films have been one-offs, such as Cannes hit Le Quattro Volte, another study of an Italian pastoral idyll. Or Werner Herzog and Dmitry Vasyukov’s Happy People: A Year in the Taiga, whose simple pleasures included watching a Siberian fur trapper make a tree into a pair of skis with just an axe. Not to mention “slow cinema” works such as Lisandro Alonso’s La Libertad (on an Argentinian wood-chopper), or Ben Rivers’ Two Years at Sea (on a Scottish hermit).

Now, though, the frequency seems to be increasing. This year’s best documentary Oscar winner, My Octopus Teacher, tapped into a similar sentiment, as a film-maker turned his back on his stressful career in favour of therapeutic natural engagement. Still in cinemas are the captivating Gunda, following a farmyard sow and her piglets in amazingly intimate detail (you could call it a “fly on the sty”), and the Sundance winner Acasă, My Home, about an unconventional Romanian family cast out from their Eden on the edge of Bucharest.

In an ideal world these films might prompt us to take action to preserve these landscapes and lifestyles, or at least question our own broken relationships with nature, but if we lived in that world, we wouldn’t need films like The Truffle Hunters. It’s a sure sign that something is broken when our fantasy is reality.