In ‘The Truffle Hunters,’ Old Masters of a different sort of art

Boston Globe

04/07/2021

Back

By Ty Burr

Some meals and some movies are good for what ails you. Some fungi, too. “The Truffle Hunters,” a documentary at the Kendall Square Cinema, follows a group of men, most of them elderly, who are the keepers of a venerable tradition. With their dogs — who are often closer to them than immediate family members — they head into the woods of northern Italy, searching in remote areas for Tuber magnatum, the prized White Alba truffle. The movie, a balm for the senses and the soul, celebrates and discreetly mourns an activity that stretches back to antiquity and is slowly being snuffed out by global market forces.

The editing puts this dichotomy up front. The opening shot could come straight from a Bruegel painting: a steep hillside in which can be spied a pair of sniffing hounds and the small figure of a man toiling upward in their wake. The next shot is of the antiseptic office where Gianfranco Curti, an elegant truffle salesman, pitches the fungi that the dogs dig up to wealthy clients and five-star chefs around the world. Among other things, “The Truffle Hunters” is a portrait of a food chain stretching from the earth to the tables of presidents.

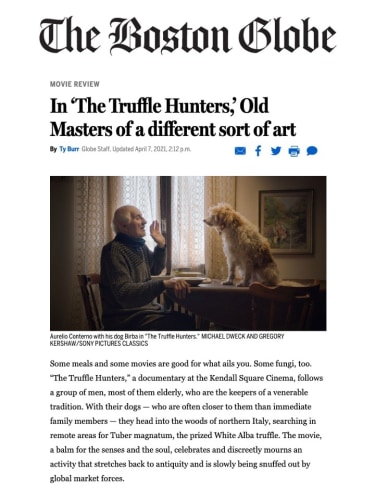

The old men — Carlo, Aurelio, Sergio, Egidio — keep the old ways as best they can, heading out to secret spots and returning with fungal gold, for which they’re paid a fraction of what a shapely truffle earns at auction. The stakes are high, and interlopers are muscling in with poisoned bait for the dogs. Aurelio is wined and dined in a charming early scene by a young man eager to learn where the old man finds his truffles before death takes him. Aurelio laughs: “Never! If the knowledge is lost, it’s lost.”

Most of them are unmarried; the exception is Carlo, 88, seen sitting at a table washing tomatoes with his wife in one silent, long, and lovely image. (It feels like they’ve been sitting there for centuries, could be sitting there still.) He favors truffle hunting with his dog, Titina, in the dead of night; the wife, Maria, fearing for his safety, lays down the law: only daytime excursions from now on. But Carlo is an outlaw by nature.

The hunters’ primary relationship is with the dogs: Titina, who in one scene is brought to church to be blessed by the priest; Aurelio’s Birba, a small, sad-eyed spaniel who sits atop a table to be fed by hand; Sergio’s Fiona and Pepe, enthusiastic hounds who become the filmmakers’ cameramen — camera-dogs — when outfitted with a snout’s-eye-view minicam. By putting us behind the eyes of a dog racing through the underbrush, happily going about what it understands as its work, “The Truffle Hunters” brings us to the source itself: the sniffing out, the digging, the discovery, the reward.

By contrast, the buyers at a fancy auction seem dispassionately removed, and by the time a truffle is shaved onto the plate of Paolo Stacchin, an impeccably dressed truffle “authenticator,” it has become the property of kings and connoisseurs — pure sensuality on a plate.

The hunters eat truffles, too, just in more humble settings. Directors Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw often capture them at home in postures that consciously evoke Old Masters like Rembrandt and Vermeer, with light streaming in from casement windows on the left. Such images tie the men to history as surely as the truffles and the dogs tie them to the soil. At one point, Sergio stands in a clearing with another hunter, reminiscing about hounds he has known. “That dog deserves a monument,” he says about one especially well-loved animal. This movie is it.

★★★½

THE TRUFFLE HUNTERS

Written and directed by Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw. At Kendall Square. In Italian, with subtitles. 84 minutes. PG-13 (some strong language)