How the directors of The Truffle Hunters caught a secret subculture on film

Dropbox for Filmmakers

01/22/2020

Back

By Drew Pearce

In August 2017, Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw, directors of the new Sundance documentary The Truffle Hunters, were traveling through northern Italy on separate trips when they coincidentally came across the same intriguing village.

After returning home, they realized they’d both heard murmurings about a group of mysterious old men who knew the secret to locating a treasure sought by chefs around the world: the Alba white truffle.

“When we were there in the summer, people actually didn't know who they were,” says Dweck. “They kept talking about ‘these men.’ Some trattorias would say they leave money in a little box. Then there would be a truffle there and the money would be gone. That kind of piqued our interest.”

Dweck and Kershaw spent a long time researching to find out how they could meet some of the mysterious hunters who guarded the secret of the truffles.

“It took about a year before we were able to penetrate this interesting subculture,” says Dweck. “The first people we met, we thought were truffle hunters, but they really weren't. There are some people that are like truffle hunters for the tourists. They simulate a truffle hunt. They dress in these outfits and have these fancy mustaches and little badges and stuff. But we learned they weren't the real ones.”

The first real truffle hunters they met were an 86-year-old named Aldo and his 90-year-old friend Renato. “When we sat with them, they were both pruning grapevines for the winter. We asked one question: ‘Where do you hunt?’ They said, ‘We're not gonna say.’ We asked, ‘How long have you guys been friends?’ They said ’80 years.’ We said, ‘You meet each other every day for breakfast and lunch. Do you ever talk about if you found any truffles or not?’ They said, ‘Never.’”

“Everything about this world, it's all secret,” says Kershaw. The restaurant owners don’t talk about their truffle suppliers because they don’t want them selling to anyone else. The hunters protect their privacy because they don’t want anyone else to know where they find their treasure—which is why they hunt at night.

“They don't want people to see where they parked their cars,” says Kershaw. “They hide their cars. They cover their tracks. They don't use any flashlights. They're out walking, sometimes 20 miles a night with a dog with no lights in the mud—and these guys are late 80s, early 90s.”

Even the sales happen under cover of the night, in black markets on secluded streets at three o’clock in the morning.

“The whole town is black, but there’s this one street, and everybody knows to go there a certain time on a certain morning every day of the week,” says Kershaw. “This whole street fills up with truffle sellers and truffle buyers. They're all making these deals. You go up and ask what they're doing and they run away from you. It took us a long time to build the trust of these communities to let us in, let us film, and let us see the things that no one else sees.”

The unconventional culture inspired the directors to take an unconventional approach to their film. Unlike most documentaries, The Truffle Hunters isn’t built around interviews. Instead, each scene is one uncut take that’s designed to feel like a painting. This was also inspired by the beauty of the natural light they found in their location.

“We wanted the audience to observe this place and the way that these people live,” says Kershaw. “That's why the camera never moves. It’s locked on frame with the exception the cameras we had mounted on dog heads. There are a couple of moments in the film where you get the POV of the dog. We developed a whole rig for dogs to be able to have a camera. But that's the only time the camera really moves.”

Kershaw says the look of the film was a response to the world around them. “This whole area where we were filming, the people that are there, the way the landscape looks, the way the homes are built—it feels like you're stepping into this magical fairytale land. We realized that we needed to create a film that felt like a storybook. So each frame we constructed in the film, we felt like ‘This is a page in that story book.’ As you go through the film, you're turning the pages in the story book and revealing the stories.”

The narrative of the film came directly from the truffle hunters themselves. “Through following them, their story slowly began to unfold,” says Kershaw.

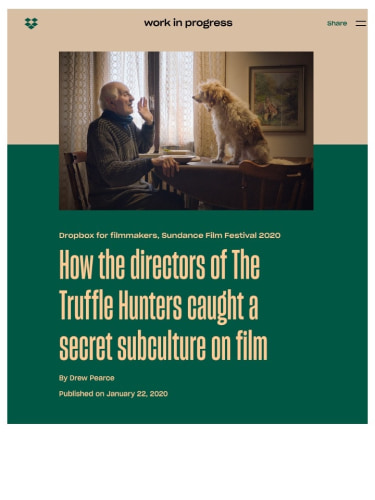

“One of the things that we didn't expect when we went into the film was the depth of the relationships that (the hunters) had with their dogs,” says Kershaw. “Some of them spent 12 hours at night alone in the woods with their dogs. As we were filming, we realized that the dogs were our characters also. A lot of times, (the hunters) don't have children or wives that are there anymore. So they confide in their dogs about what's going on in their lives.”

Another unexpected discovery was the almost total absence of modern conveniences.

“They don't really interact with technology at all there,” says Dweck. “They don't have television sets or computers. Rarely do we see a phone there.”

It was a quiet, simple life the directors didn’t want to disrupt by bringing in a large crew with lots of equipment.

“We wanted the experience of filming to be pretty intimate,” says Dweck. “It was just Gregory, myself, a sound person and a translator. That's it. There was nobody else there. It was difficult for us, but also, it helped us. They didn't really realize we were there in the room. We were just guests in their home.”

As a result of keeping the crew small, much of the production work had to be sent to crew members based in other parts of the world.

“Everything we did was remote,” says Dweck. “Gregory lives in Stockholm, I live in New York. Our assistant editor is north Macedonia. Our editors live Copenhagen. We shot in Italy.”

“When we would meet up, we would meet in various places around the world,” adds Kershaw. “We were constantly in motion and constantly remote.”

“And we had to get everything translated,” says Dweck. “So we had five translators living in different parts of Italy. In Macedonia, we had an assistant that had to take all of our translations and map that to a picture. That picture had to go to the editor, then us, so we could edit from the conformed picture in subtitles.”

“10 years ago, we didn't have this technology to share it,” explains Dweck. “We would have had to ship hard drives all over the place. The pace at which we were operating, this film would take another year, probably, if we didn't have the technology. All the translators were communicating with our assistance and with us all through Dropbox.”

Meanwhile in the village, the hunters continued thriving in their decidedly offline lives—and seemed all the more vibrant and interconnected for it.

“One of the great things of filming this generation is their lives,” says Kershaw. “They don't watch reality TV. They don't have a preconception about what a documentary film is. We would bring the camera into the world, and they would immediately almost forget about us and go about their day-to-day life in a way that I think it would be very difficult to do elsewhere.”

Kershaw says this discreet approach allowed them to capture moments they might otherwise have missed. “One conversation in the film is between husband and wife and she's saying to him, ‘You're approaching the end your life. You're seventy years old. If you get hurt, you can be a burden to the family.’ He says to her ‘What if this is only the beginning? What if we can start all over again’ He really believes he's just going to keep going. I think the film is also about living forever because of the passion.”

“We went into it thinking we were making a film about old men confronting their own mortality,” says Dweck. “What we realized is, they actually behave like young men. In a lot of ways, it's a film about people that have retained their youth. They live like they’re 20 year olds. They still kind of live in that era. We felt like we were stepping back in time, into the days of their youth. That was the music that surrounded them. That was the technology that existed for them. It's not digital technology. It's analog technology. We tried to bring that feeling into the filmmaking.”

“When we started filming this, we knew that there was this mystery,” Dweck explains. “That was that was what got us into it. But we didn't really know what the story was about. As we spent time with our characters, we realized it was a story about passion. It was a story about people who persevere and keep on living. Their lives are rich and full. At the time we started filming, we didn't know how life-affirming the story was going to be. As it’s coming together now, we realize that the story is a celebration of life. It’s hard to find stories like that in the world right now, that show you something to live for, that show people who have found a way to live. So that's been one of the real pleasures of seeing this all come together.”

The Truffle Hunters premieres January 26 at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival.