Gaucho Gaucho Review: Nostalgia for a Fading Way of Life

POV Magazine

01/23/2024

Back

By Jason Gorber

2024 Sundance Film Festival

Gaucho Gaucho

(USA, 84 min.)

Dir. Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw

Programme: U.S. Documentary Competition (World Premiere)

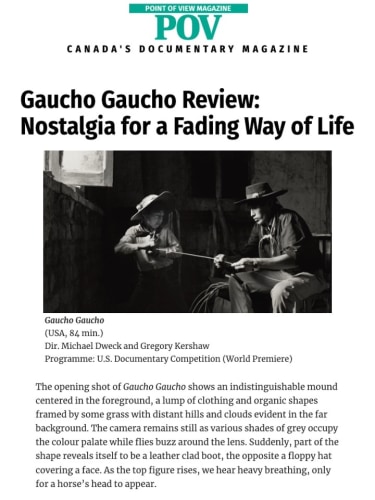

The opening shot of Gaucho Gaucho shows an indistinguishable mound centered in the foreground, a lump of clothing and organic shapes framed by some grass with distant hills and clouds evident in the far background. The camera remains still as various shades of grey occupy the colour palate while flies buzz around the lens. Suddenly, part of the shape reveals itself to be a leather clad boot, the opposite a floppy hat covering a face. As the top figure rises, we hear heavy breathing, only for a horse’s head to appear.

This was a gaucho, one of the legendary Argentine ranchers, with his trusty steed, demonstrating the remarkable connection between man and beast that’s long been evocative of these characters. The quiet is replaced by an operatic vocal and tracking shot from left to right, men on horses ride in slow motion while their dogs follow behind.

It’s perhaps unsurprising that this same movement was presaged by the production company bumper for “Beautiful Stories,” with another dog in slow motion moving in the same screen direction. For Gaucho Gaucho is indeed beautiful, and it is a non-fiction film unencumbered from being overtly as story, leaning heavily into genre tropes while nonetheless exposing in ways both subtle and overt the lives of those in this community of ranchers. Even the marketing of the film leans into the mythmaking, with a stunning hand-painted poster that immediately evokes the cowboy films that dominated early Hollywood, the names of the documentary subjects highlighted like matinee idols of yore.

Directors Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw have already demonstrated their bone fides when it comes to having taciturn communities expose a dose of their unique circumstances. One need only look to 2020’s sublime The Truffle Hunters for such a taste. Here too the filmmakers embed with Mario, Wally and others to give a sense of life on the plains. Guada’s own journey as a young woman pushing to tame wild horses provides one particularly redolent metaphor, as does Lelo’s own existential ruminations about aging and the changes that have occurred over a lifetime.

We watch as one of the gauchos talks to the local priest, a stark statue of Jesus in the background, as he is asked how he would like to be remembered: As copla singer? As paperboy? As radio presenter? As a musician? As a folklore dancer? “Just Santito,” the man replies. “May Santito mean all that.” This is but one of many vignettes that feel both immensely truthful and as crafted as any staged story line, a mix between actuality and performance distilled into a combination that reveals deeper truths.

The journey of young Guada as she defies the dress code restrictions at school and stands distant and sullen away from her peers could almost be part of a John Hughes movie. A smash cut during one of her riding adventures, used with concern for the off-screen crowd, presages an injury. These among the film’s many sardonically comical moments, including when we hear tales of condors gutting young calves from tongue to stern while men sit at a table with a splayed bird decorating the wall behind.

Yet the filmmakers manage, it seems, to elevate these quotidian moments without ever dismissing the faithfulness to the experiences or the actual lifestyles of these subjects. There’s a dance between the richly cinematic imagery that immediately evokes the past and a very contemporary sense of how forces outside the community are forcing changes, some welcome, some less so.

At best we are getting a taste of what life is like for these gauchos, and in many ways, it’s an existence that they present to visitors, the audience included. Yet more subtle elements are at times glimpsed, breaking through the façade to find powerful truths from those who maintain a way of life that in much of the world is now truly extinct.

There’s nothing luddite or contrary about the life of the gaucho that’s on display, and this isn’t some mere fetishization of life on the plains. Instead, we see glimpses of self-reliance buttressed by self-examination, with younger generations mimicking the ways of their elders and in so doing keeping something as deep as tradition alive.

Similarly, their companion animals, like in Truffle Hunters, provided a deep symbiotic connection that goes well beyond the modality for many people in modern society. Yet even here we see times for sport, a rodeo event as common in this area as it would be in the Southern U.S., broncos ridden for the delight of spectators to see what these individuals can accomplish for vicarious thrills.

The film provides a kind of formalistic tango between its disparate elements, re-emphasised by the deliberately archaic black and white cinematography that captures these moments with an overly cinematic distance. This choice situates even the most banal of events with a grandeur that feels worthy of wide-screen celebration. The result is an aesthetic marvel that provides a sweeping canvas for these seemingly simplistic vignettes to occupy.

Seen in its totality, Gaucho Gaucho provides a fascinating mix of adventure and ennui, a dose of nostalgia underscoring what at times may be a pessimistic view of what’s to come, and at other moment, an opportunity to continue to flourish into the future. It’s this deft, improbable balance coaxed out by the filmmakers, the same kind of balance we experience with the charismatic character at the start of the film laying atop his horse, which gives the movie much of its magic. The result is a stellar experience, presenting in stunning ways the beauty of these people and their environs, while equally encouraging audiences to listen closely to the truths of their experiences that they dole out in small measure.