All the Way to Heaven

Bright Wall/Dark Room

08/09/2024

Back

The Truffle Hunters (2020)

Catherine Ellsberg

Midway upon the journey of our life,” Dante wrote, “I found myself within a forest dark, for the straightforward pathway had been lost.” I thought of these lines from Inferno as I watched Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw’s documentary The Truffle Hunters (2020), set in the northwest Italian region of Piedmont. Unlike Dante, though, the titular characters of this beautiful, wistful film seem to know exactly which path to take to uncover the region’s prized white Alba truffle. Surrounded by scrub woods and muted brown and green thickets, our octogenarian heroes nimbly forage through forests in the dead of night (the better to guard secret locations), aided only by a flashlight and, most importantly, by their trusted dogs. At its heart, The Truffle Hunters is a profound, poetic reflection on man’s friendship with animals, the evils of corruption and capitalism (which they would argue are inseparable), and our tenuous place on a warming planet.

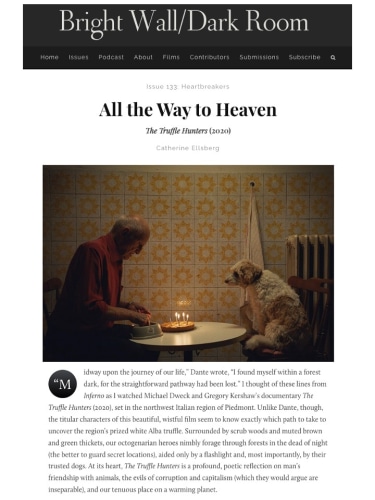

Released in 2020, The Truffle Hunters exists in a space beyond time. The central truffle hunters, or tartufai, live in small, plainly decorated houses that could easily have existed 150 years ago. The interiors are splashed by pinks and bright yellows; the setting is bare, if not austere. A curly-haired Sergio sits in a bathtub with his dog, blow-drying his coat, against a backdrop of bubble gum pink tiling. An elderly couple pose in the foreground, washing a mound of bright, crimson tomatoes, plants unfurling behind them in their aqua green kitchen. “Oh, I love fresh tomatoes so much,” Carlo says to his silent, perpetually frowning wife. Each shot is static, stationary (reportedly, there are only 107 shots in the whole film) and yet, the frames teem with life and the flurry of unspoken feeling.

Somehow, while observing the chiaroscuro shots of the elderly men, typing away on an Olivetti or offering a bowl of broth to their dogs at the table, I had the feeling that I knew them personally. I had always identified more strongly with the Eastern European shtetls of my other genetic half and had paid no heed to my Sicilian grandfather, Michael Rizza, who came to Ellis Island at age five. And yet, while watching The Truffle Hunters, I felt a sensation of uncanny familiarity, perhaps explained when my mother told me that the other side of her family came from Turin—the capital of the Piedmont region where the film is set. And so, the eccentric, bearded Angelo, who has sworn off truffle hunting for good following the death of his beloved hunting dog, Siana—to whom a “monument” should be built, a neighbor proclaims—or the 84-year-old Aurelio feeding from his own mouth his beloved, furry Birba, embody an inexplicable, comforting aura of family.

The personal link does not end there. I watched The Truffle Hunters alongside my own truffle-hunting Lagotto Romagnolo puppy, Larry. As Italian as a bowl of Buca di Beppo spaghetti, Larry was named after Larry David; he shares with his namesake a remarkable sense of etiquette and social mores (when or if to beg for food, when it is appropriate to sniff a comrade’s rear end, etc.). Chocolate brown with white patches and covered in small ringlets, Larry resembles a sturdy teddy bear. My path to finding and procuring a Lagotto was happenstance and involved, in classic Millennial fashion, an online quiz. I wept tears of joy when I saw the 100% matched images of a curly, stout, and rustic dog called the Lagotto—I knew I had found my best friend.

The nugget of trivia offered on the American Kennel Club site—that Lagottos were prized and internationally renowned truffle hunters—seemed but a minor bonus detail. Little did I know that Larry would manifest his skill in such unexpected, and insistent, ways: upon our multiple daily walks, Larry keeps his nose to the ground, sniffing out invisible truffles. Except, instead of rooting out the rare fungi on my Parisian street, he devours anything and everything in sight—shredded plastic, discarded tissues, and even, on one traumatic occasion, an unwrapped condom outside the local health clinic. In this way, Larry resembles less the famous tartufai of his homeland and more the voraciously hungry, undiscerning pigs that were used by hunters of black truffles in Renaissance-era Italy and France.

For this reason, I wisely choose not to kiss Larry directly on the snout, as Aurelio, Carlo, and Sergio often do to their canine partners in the film. The men seem to walk in step with their dogs, to connect on a metaphysical level that extends beyond the petty restrictions of money and greed that threaten their livelihoods. Indeed, while these tartufai toil at all hours of the night and early mornings to hunt for a few misshapen truffles, they barely earn a few hundred euros for their findings. In contrast, the vendors—always seen selling and trading their wares to flashy international clients in either sanitized, windowless rooms or in dimly lit, dusky town corners (not unlike drug dealers)—easily rake in 4500 euros for a few hundred grams of the precious mushroom.

These vendors are missing the point entirely, as the bearded, gangly Angelo argues at several reprises. In many scenes, men try to persuade the out-of-the-game Angelo to return to searching for truffles across his sizable acreage. Angelo repeatedly refuses. At one point, he types away in a cavernous-looking room, a crucifix and stacks of yellowing books behind him, a manifesto: “I want to write down why I want to quit truffle hunting…. I want to quit for one reason—there are too many greedy people. They don’t do it for fun or to play with their dogs, or to spend some time in nature. They only want money.”

Corruption and avarice are the true evils of the film and, the men would surely claim, of our fragile ecosystem. So driven and spiteful are certain hunters, that they go to the horrific lengths of poisoning the earth with strychnine to stave off innocent dogs digging for truffles. Angelo is rightfully disgusted by such men, clacking on his Olivetti: “If I catch one of those [men], I’m going to hang them on a tree upside down.” The threat of this awful crime looms over the entire film; at one point, we witness Sergio going to a craftsman to tailor for his beloved dog a special muzzle to protect her nose from the poison. At other points the elderly men stand in circles, remembering dogs already lost with elegiac reverence. Eventually, the worst will indeed come to pass: Sergio’s dog will succumb to poison, as he recounts while breaking down to a local policeman. We never actually see the culprits, but it is clear that they are part of a mercenary system—characterized by portly truffle “judges” and smooth-talking salesmen—that squeezes profits and luxury goods out of the innocence of these dogs.

This cocoon-like world is almost entirely masculine. “You know what I was thinking?” the 84-year-old Aurelio whispers to his only female companion, the golden-haired pup named Birba. With no desire to pass along his truffle locations—thus denying younger generations a chance to continue the tradition of the hunt—his sole, real concern in life is to find a new family for his dog after his inevitable death. “If we find a wild woman,” he coos, “because, you know, there are some good ones, but they’re rare…I will leave her the house, and she will take care of you.”

The only woman we ever meet (other than some Melania Trump-like truffle aficionados) is Carlo’s wife. Described earlier, during the scene of washing tomatoes, this Italian matron is so precise, so specific; I can picture my own nonna—scowl on her face, a dexterous chef—and imagine her interactions with the grandfather I never knew. “Carloooo,” the wife yells out the window after her absent, sidetracked husband. Later, at the dinner table, she beseeches him to stop truffle hunting—at the very least, to quit going in the dead of night, when the 87-year-old could easily injure himself. “Why won’t you stop truffle hunting? Why are you so stubborn? Stay at home. Especially at night. You might fall and hurt yourself. Then others will have to take care of us.” “But,” Carlo insists, “I like it at night…. During the night, I like to listen to the owl.” His wife remains unfazed: “You can listen to it at home.” After all, she entreats, “You are almost at the end of your life.” Without hesitation, Carlo responds—with utterly poignant clarity: “What if this is just the beginning?”

The subtle but staunch spirituality of Carlo and his dog, Titina, come to the fore in my favorite scene of the film. In a lavish and gorgeous shot in an ornate, gilded church, Carlo stands in front of a priest, Titina standing nobly by his side. “We invoke God’s blessing,” announces the priest, “May God preserve Carlo still for a long time, with full health and energy, so that he can continue his work as an outstanding truffle hunter, serving people so they can eat his truffles. And may God preserve the dog’s sense of smell, which is precious and helps with the hunt.” This sense of community—that Carlo’s rambling treks are not merely for his own pleasure, but at the service of others—is beautiful, if fleeting. After all, the priest later reminds Carlo, “Eventually we are all going to die.” But, he acquiesces, “I’m sure that you will keep on hunting truffles” in the afterlife.

“All the way to heaven is heaven,” said St. Catherine of Siena. While hunting truffles, these men are already in a kind of earthly heaven—at once precious and fragile. Throughout the film, there are several scenes where a small camera is attached to the furry hunters: their noses to the ground, eternally sniffing and searching for treasure, we can practically smell the crisp air across our screens. This—this is heaven, I whisper to Larry. And as the last shot of the film arrives, with Carlo crawling out his window at dawn to avoid waking his wife, in search of owl cries and truffles, we are told: this could just be the beginning.