A sweet life if you belong to Cuba's upper crust

SFGate

09/29/2011

Back

Jonathan Curiel, Special to The Chronicle / Published 4:00 am PDT, Thursday, September 29, 2011

Everyone knows that Cuba is one of the Western Hemisphere's poorest countries. Its economic indices lag in nearly every category, including gross domestic product and household income. Yet the stereotype of Cuba as a strict post-Communist backwater - a kind of Shangri-la of egalitarianism - has taken a beating in the past year.

First, there was an article in the Economist that quoted Ada Fuentes, a woman who returned to Havana after living in New Jersey for five decades. "If you have money," Fuentes said, "life's good here."

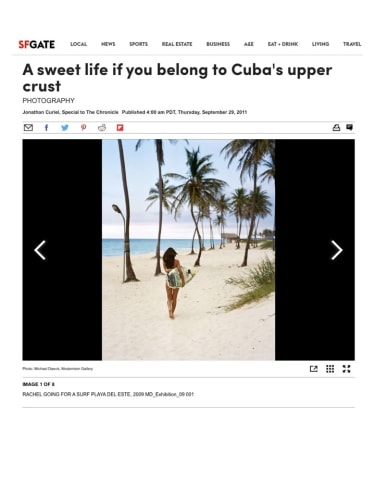

Now there is Michael Dweck's photo project that shows Cuba's privileged side - a side of beautiful models, late-night partiers, daytime surfers, hard-working guitar players and other people who make up Cuba's "creative class," as Dweck calls them. Two of Fidel Castro's sons (Alex and Alejandro) are on the periphery of this strata. So is the son of Che Guevara, Camilo Guevara, who's a photographer.

The revolution that Fidel Castro and Che Guevara brought to the island nation five decades ago has evolved into something unexpected: Guilty pleasure. As Dweck notes in his new book, " Michael Dweck: Habana Libre," some of the people he photographed are "embarrassed" about their relatively elite standing; others, he says, "are afraid to draw attention to it for fear the socialist government will punish them for having a good life." An exhibit of photos from "Habana Libre" continues at San Francisco's Modernism gallery through Oct. 29.

"Artists, writers, filmmakers, dancers - they live this secretive life under the radar in Cuba that is really cool and lends itself well to a narrative," says Dweck. "I'm playing on the theme of privilege in a classless society."

Not surprisingly, some Cubans didn't want to cooperate with Dweck. One woman he met there told him, "I think this project is going to get a lot of people in trouble, and you're on your own." But Dweck, based in New York City, was never really on his own. Within hours of first flying to Havana, he befriended a well-connected British expat who told him about a private party at an old 20,000-square-foot oceanside residence, where Dweck met Cubans he would photograph for "Habana Libre."

From then on, Dweck was invited to other private parties, then - eventually - to his subjects' homes and sanctuaries. Painters Rene Francisco and Carlos Quintana took Dweck to their studios. Camilo Guevara is in his house. Rachel Valdes, an accomplished model and painter, is among those photographed with little on as she goes about her business.

"I got lucky, and they were nice to trust me," says Dweck, who visited Cuba eight times from 2009-2010.

People who know Dweck's earlier photographic work will recognize a pattern with "Habana Libre": Water and nubile women (and men). In 2004, Dweck published "The End: Montauk, N.Y.," which featured topless beachgoers posing, cavorting and rushing to their destination - a scenic tapestry that evoked, Dweck said, "the paradise of summer, youth, and erotic possibility." Dweck says his photos - whether he's in Havana, Montauk or New Mexico's White Sands Missile Range (shooting shiny weapons of mass destruction for his next project) - are often about things that hint or intimate at a compelling story.

"My work is very much about being suggestive," Dweck says. "For me, photography is not so much about capturing 'the moment.' My work is more about time and place and how we got there and where we're going next."

Dweck came to photography in a circuitous way. Until 2002, he was head of his own advertising firm, whose best-known TV spot, "Arctic Ground Squirrel," featured a caustic man dressed as a squirrel getting a mattress delivered to his winter house in Brooklyn. (The man wants to "hibernate" to get away from his nagging wife.) The ad still makes the rounds on YouTube and other video sites, and the Museum of Modern Art owns a copy.

Dweck garnered scores of awards for his advertising and did work for "The Daily Show" and "South Park," but he left it all behind ("at the peak of my career") to pursue photography full time, drawn soon after by capturing Montauk life while the Long Island community was unchanged from his teen years there. Dweck's Montauk photos were initially shown on the sixth floor of Sotheby's - the first time the New York auction house had devoted an exhibition to a living photographer.

Since then, Dweck has garnered a portfolio that any photographer would dream of: Images in publications like Vanity Fair and Esquire; a series of well-reviewed books; and gallery shows around the world, including Tokyo, Belgium and Hamburg.

For Dweck, Cuba was the embodiment of everything he lives for. "I'm always attracted to subject matter that has seduction in it, and Cuba, to me, has all the elements of a seductive subject," Dweck says. "It's dangerous, it's mysterious, it's playful, it's subtle, it's sensual."

It also has name recognition. For an older generation, the name "Cuba" instills immediate associations with Castro, the 1962 missile crisis, and a long-standing American embargo that has helped keep the island isolated economically.

Dweck's photos are a jarring update of Cuban society. The Cubans in "Habana Libre" are able to express themselves through their art and the way they live. Young in spirit if not in age, they wanted Dweck to know that Cubans on the island can transcend their economic limitations. For these Cubans, "the good life" is never far away.

"Michael Dweck: Habana Libre": The photo exhibit runs through Oct. 29. Modernism, 685 Market St., Suite 290, Tues.-Sat., 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Information: (415) 541-0461 or www.modernisminc.com.